Addition Therapeutics has emerged from stealth with $100 million in hand to develop new types of gene therapies that might work against rare as well as chronic diseases.

Spun out of research at the University of California, Berkeley, the startup is pursuing genetic medicines intended to work differently from existing approaches and, in the process, overcome some of their key limitations.

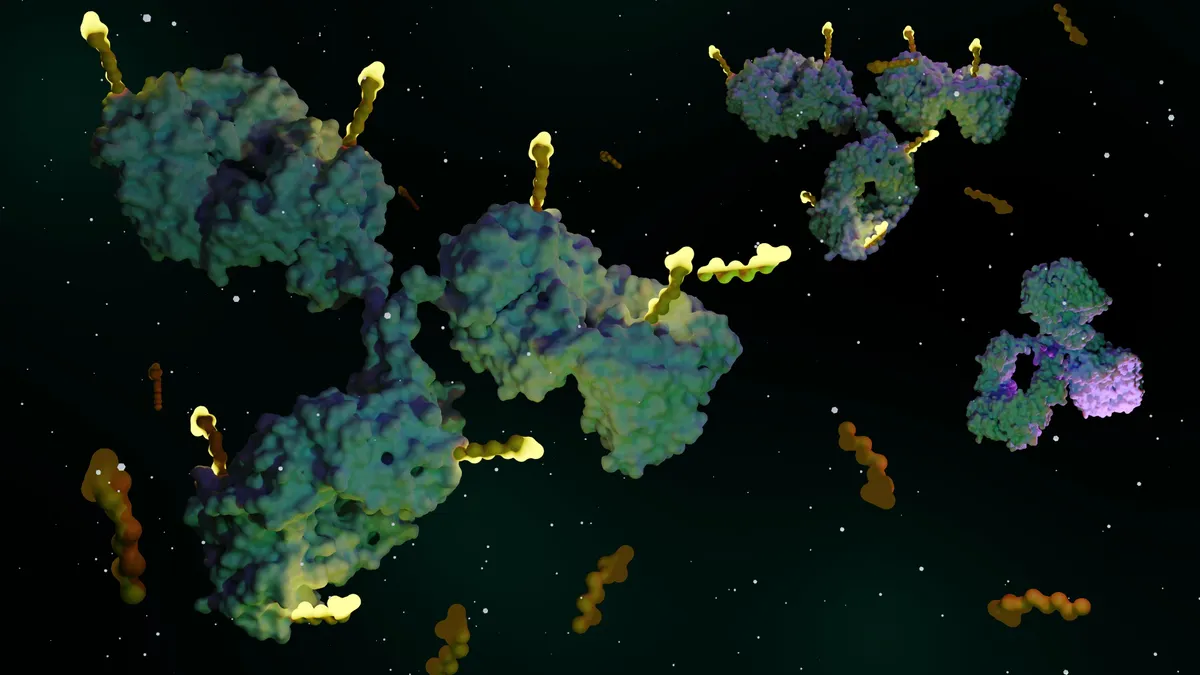

The gene therapies and gene editing treatments that have come to market so far are essentially blunt tools. Gene therapies typically work by delivering into cells genetic cargo to replace malfunctioning genes and produce a helpful protein. Editing tools such as CRISPR can cut into DNA to inactivate or fix a problematic gene.

Those methods have proven helpful in treating many rare diseases. But they all have drawbacks. They are largely costly to produce and may only help a small fraction of patients with a disease. To deliver their payloads, they often rely on engineered viruses that can provoke unintended immune responses that shut down a treatment or cause safety problems.

The effects of gene therapies can also wane over time. And CRISPR drugs, while promsing more permanent changes, can make wayward edits that cause harm, too.

“It’s really tough and expensive to develop your therapies, and for the end of it, the patient population that it can address is relatively small,” said Ron Park, Addition’s CEO. “That creates a business model for traditional gene therapy approaches that is just very, very difficult.”

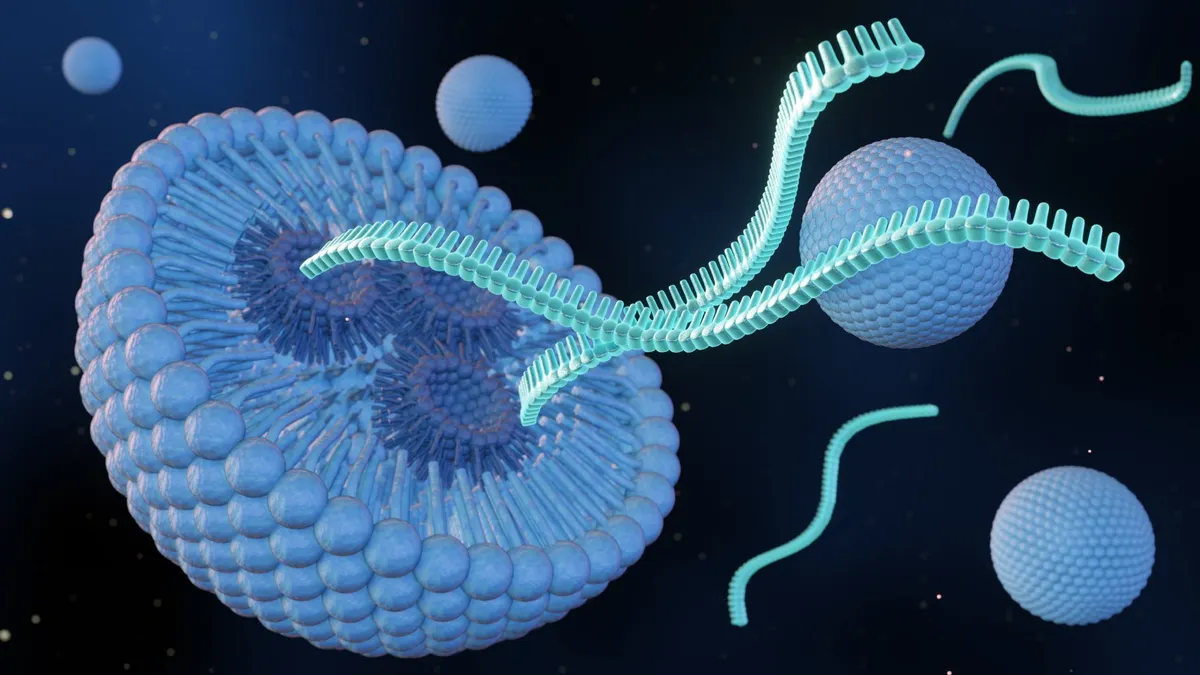

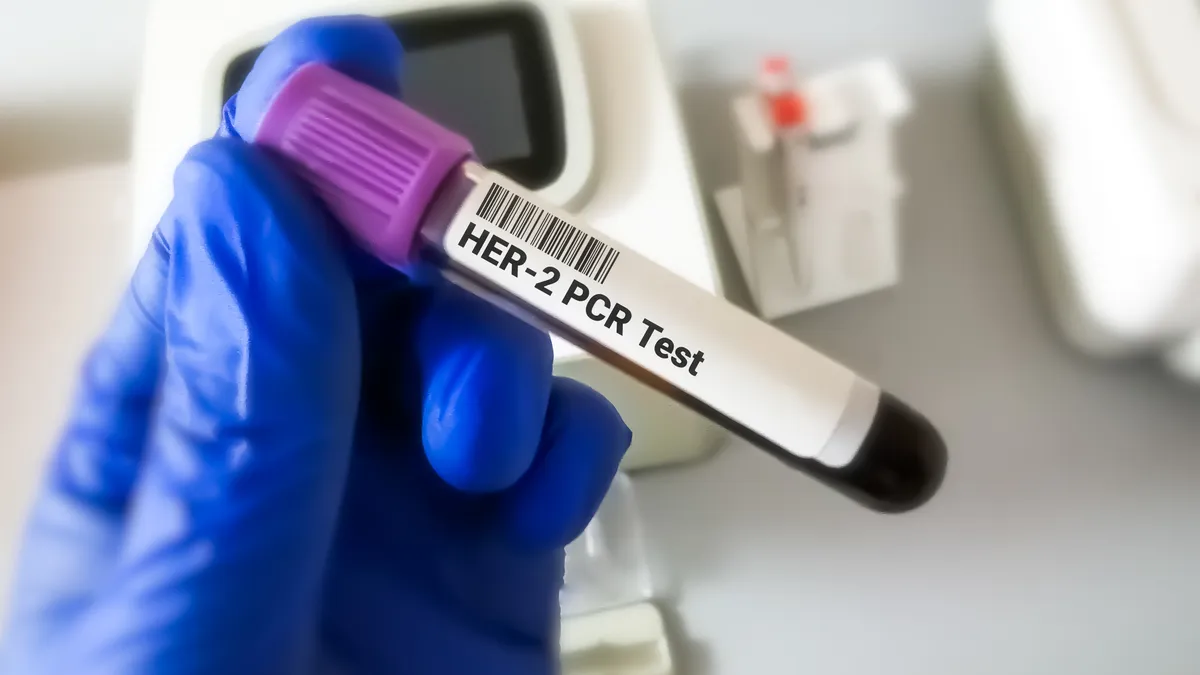

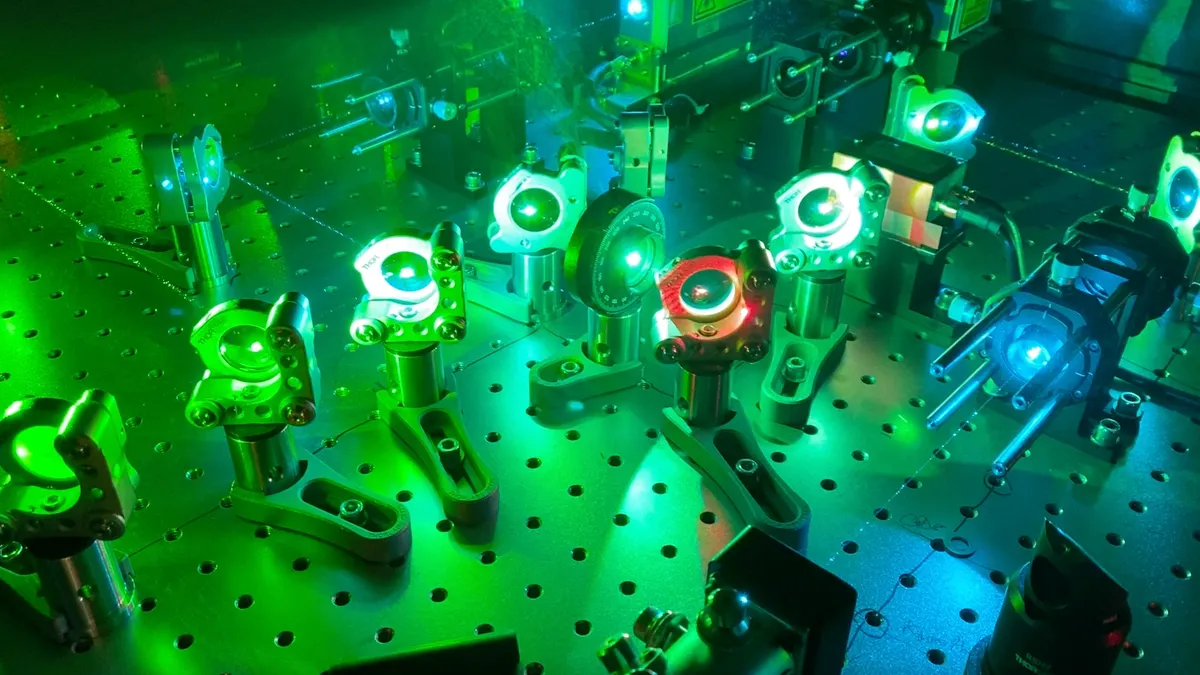

Addition aims to sidestep these issues with a different approach. It’s using fatty shells known as lipid nanoparticles to deliver into cells a type of RNA bound to a specialized enzyme. Once inside, the enzyme copies the RNA message into DNA, which is then directed to a specific region of a cell’s genome.

The result should be treatments that are safer, more durable and cheaper to produce than those made from conventionial methods, said Francine Gregoire, Addition’s chief scientific officer. The company believes it to be applicable to not just rare diseases but more common ones, too, which could make “the whole model work much better for the whole ecosystem,” Park added.

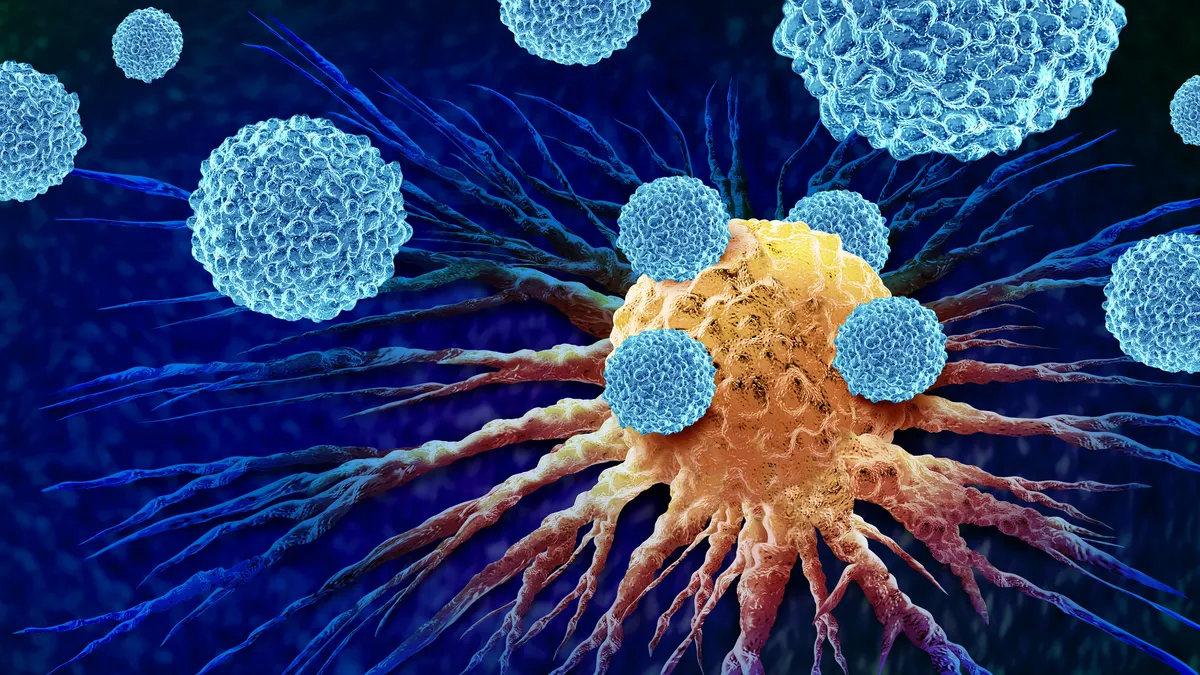

One example of the latter is HIV. Addition is working with one of its investment partners, the Gates Foundation, to create an HIV treatment that spurs the body to express protective antibodies for life.

Park said such a product could be particularly helpful for people at high risk of contracting HIV, and potentially helpful in those who already have chronic disease, too.

A half dozen investors backed Addition’s Series A round, including SR One, Pivotal Life Sciences and Abingworth. Formed in 2021, the company hasn’t yet disclosed its other disease targets, though it said in a statement that multiple pipeline programs are being funded through research initiatives with unnamed pharmaceutical companies.