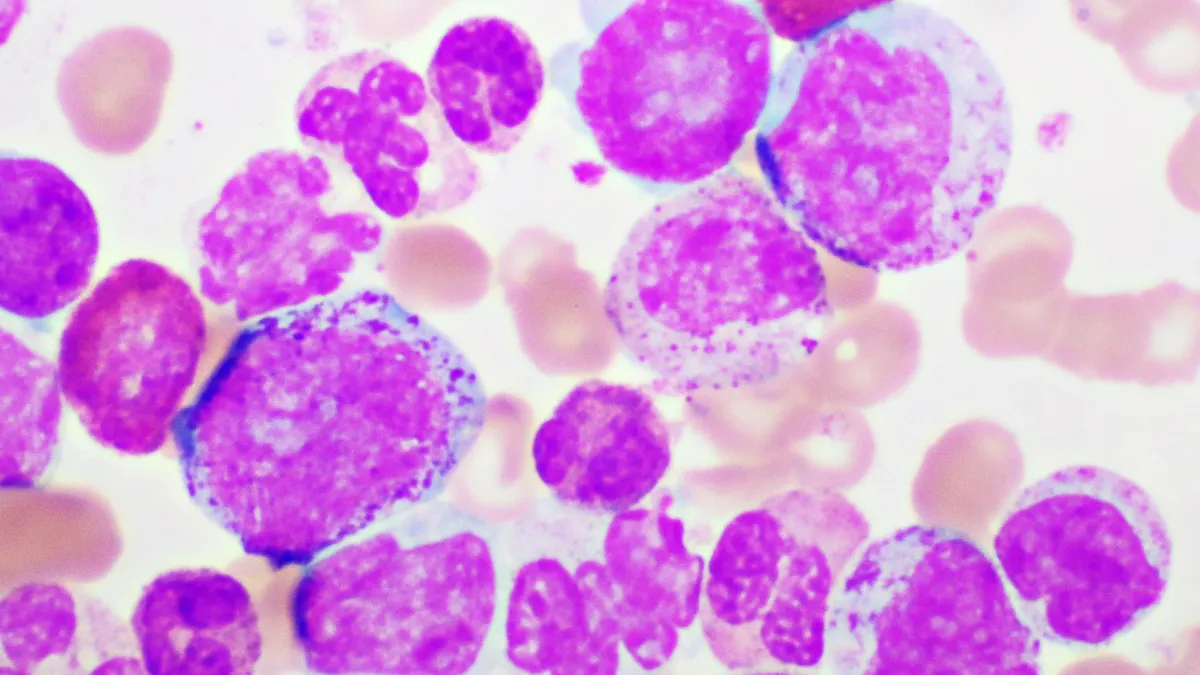

ORLANDO — An experimental drug from Terns Pharmaceuticals is showing it may emerge as a threat to multiple established medicines for a slow-growing blood malignancy known as chronic myeloid leukemia.

According to results presented at the American Society of Hematology meeting on Monday, Terns’ drug, codenamed TERN-701, helped a majority of study participants with CML who had received previous treatments significantly reduce the number of diseased white blood cells in their bloodstream. The findings suggest the drug, a type of targeted, oral treatment, may eventually be competitive with widely used medicines like Novartis’ Scemblix, which is expected to generate more than $4 billion in peak yearly sales.

Terns first announced a small cut of data from the trial in early November, claiming at the time that the efficacy findings were “unprecedented” among marketed and experimental treatments for CML. Company shares have more than tripled since then, heightening anticipation for the detailed results being presented at ASH. TERN-701 “could potentially upend Scemblix dominance” in CML, wrote William Blair analyst Andy Hsieh, in a research note last month.

The study, called CARDINAL, is primarily evaluating the safety of TERN-701 in people who’ve received prior treatments such as Scemblix or another Novartis medicine, Gleevec, as well as determining which dose to advance into further testing. Nearly all of the study recruits joined the trial because their previous treatments stopped working or had too many side effects.

But investigators also measured “molecular response,” or how much the drug reduces the share of cells containing the aberrant BCR-ABL gene that drives the disease. Molecular response rates are frequently used as a study endpoint for CML trials because it’s predictive of longer-term benefits, such as a reduced risk of disease progression.

Among 38 patients who were evaluable for efficacy, TERN-701 helped 74% attain a “major” molecular response — a 1,000-fold reduction in the percentage of white blood cells with the BCR-ABL gene — by 24 weeks. Of those who weren’t classified as being in major molecular response at the study’s start, 64% achieved it afterwards. All patients at that level when the trial began maintained that status, too.

In a similar study population, Scemblix helped 25% of trial volunteers achieve a major molecular response at 24 weeks. Cross-trial comparisons can be misleading, however, and the two drugs haven’t been tested head to head.

Still, “what it's telling us is that this is a better drug,” said Terns CEO Amy Burroughs, in an interview with BioPharma Dive. “This is going to raise the bar in efficacy.”

Updated data presented at ASH show that the occurrence of side effects and severe side effects remains low among TERN-701 recipients, with 32% of the 63 patients who entered the trial having a “Grade 3” adverse event. Only one patient dropped out of the study due to a severe side effect. No signs of high blood pressure or pancreatitis — side effects associated with Scemblix and another CML drug, Iclusig — have occurred. Iclusig also has a “black box” warning of blood clotting events that have included heart attacks and strokes.

Drugs like TERN-701 and others in its class work by blocking a signaling molecule that produces the diseased white blood cells in CML. Early drugs like Gleevec worked by blocking the active part of the molecule that prevents its signaling, while Scemblix and TERN-701 grab onto a site that changes the shape of the molecule.

The latter approach reduces the number of “off-target” interactions that can trigger severe side effects, Burroughs said.