Dive Brief:

- BridgeBio Pharma plans to trim its spending on gene therapy research by more than $50 million after early-stage study results for one of its experimental therapies failed to meet the company’s threshold for additional investment.

- Disclosed by BridgeBio Tuesday afternoon, the data showed treatment with the company’s BBP-631 therapy led to increased production of a key hormone in people with a condition known as congential adrenal hyperplasia, or CAH. No treatment-related serious side effects were reported.

- BridgeBio claimed its study showed for the first time that people with CAH can make this hormone, called cortisol and necessary for the body’s response to stressors. But “data to date are not yet transformational,” said company CEO Neil Kumar, so BridgeBio intends to find a partner for BBP-631’s development.

Dive Insight:

BridgeBio isn’t getting out of gene therapy entirely. The company has another experimental treatment for a neuromuscular disease called Canavan.

“We believe that gene therapies have the potential to fulfill a significant unmet need and are eager to work closely with the FDA and the Canavan community with the goal of bringing our therapy to families living with Canavan disease as fast as possible,” said Chief Financial Officer Brian Stephenson in Tuesday’s statement.

But BridgeBio is taking a step back from the field and, moving forward, will be “reserving gene therapy for priority targets that we cannot treat any other way,” Stephenson said.

The effect is a further focusing of BridgeBio’s pipeline around a handful of later-stage assets, foremost among them acoramidis, a treatment for transthyretin amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy that’s currently under regulatory review in the U.S. The company also has medicines in Phase 3 testing for a rare calcium disorder, a kind of muscular dystrophy and a bone growth disorder.

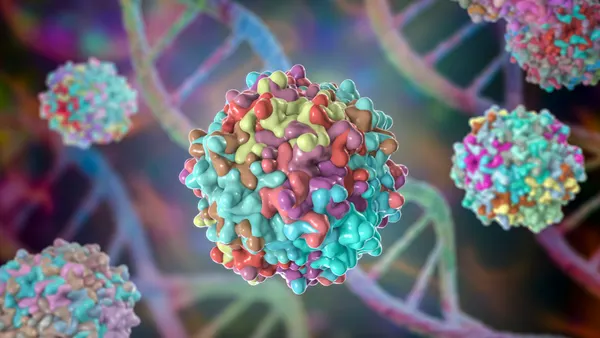

The results for BBP-631 came from the latter half of a Phase 1/2 study that enrolled adults with “classic” CAH. The study found treatment led to increases in endogenous cortisol production in all patients given higher doses of the therapy. Investigators also reported “substantial and durable increases” in the product and substrate of the enzyme that makes cortisol. This, BridgeBio said, suggested its therapy had successfully delivered its genetic payload into the body.

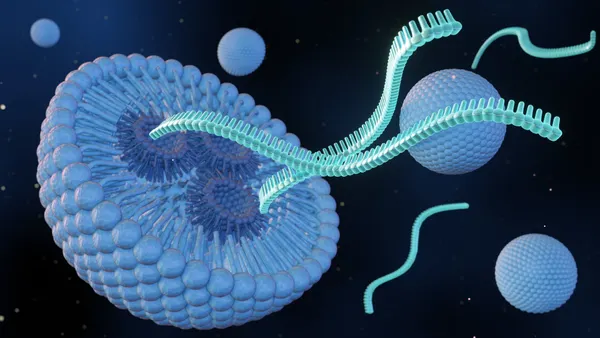

BBP-631 uses a benign form of an adeno-associated virus to shuttle a functional copy of the gene encoding that enzyme to the adrenal gland. By inducing the body to produce cortisol, BridgeBio hoped to eliminate or substantially reduce the steroid treatments that people with CAH currently use to manage their condition.