Dive Brief:

- Eli Lilly’s experimental pill for obesity helped people lose more weight than placebo in a Phase 3 study, but was less effective than Wall Street investors had anticipated, leading to a selloff in shares that erased about $100 billion from the pharmaceutical company's market value.

- Study participants given the highest dose of the drug, orforglipron, lost on average 11 percentage points more of their body weight than those on placebo after 72 weeks of treatment, Lilly said Thursday. People who received orforglipron lost an average of 27 pounds from the study’s start, compared with a loss of two pounds among those taking placebo.

- Lilly will submit the results, as well as the findings from a late-stage trial in diabetes, to the Food and Drug Administration by the end of 2025. Analysts noted that a rival pill developed by Novo Nordisk and already under FDA review had numerically higher weight loss numbers in clinical testing. Lilly shares fell 14% in early trading Thursday.

Dive Insight:

Lilly announced the results alongside its second quarter earnings report, which, on its own, might have encouraged investors. The company boosted its share of the competitive market for GLP-1 medicines, as Mounjaro in July became the most-prescribed drug of its kind in diabetes.

Mounjaro and Zepbound, the obesity drug that shares the same active ingredient, both bested consensus estimates for the quarter, recording sales of $5.2 billion and $3.4 billion respectively. The company also boosted its 2025 financial forecasts by around 3%. It’s now expecting $61 billion to $62 billion in revenue, compared to the $58 billion to $61 billion range it previously projected.

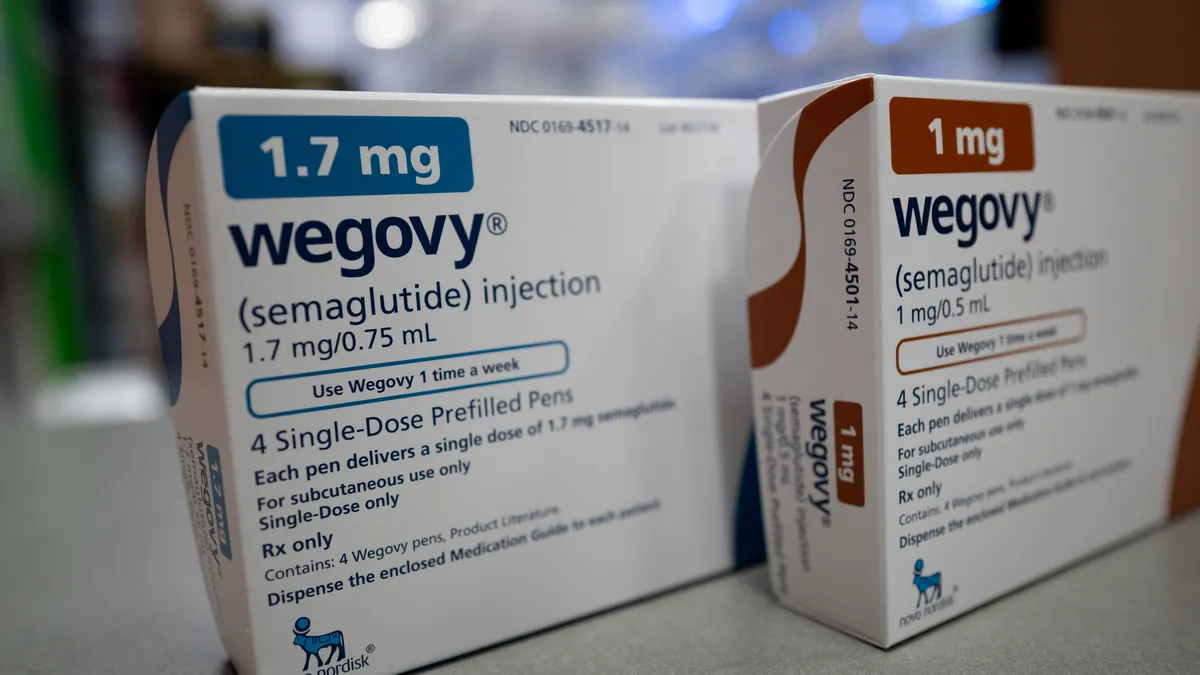

Yet the orforglipron data cast a shadow over those numbers. The drug had a more modest effects than injectable drugs like Zepbound and Novo’s Wegovy, which were associated with weight loss percentages of as much as 21% and 15%, respectively, in clinical testing. The oral version of Wegovy Novo’s advancing also achieved 15% weight loss.

On a Thursday conference call with analysts, Lilly executives contended orforglipron, because of its convenience, will still be attractive to people with obesity.

“The instructions for use here are going to be pretty simple: take it once a day, without regard to food and water,” said Kenneth Custer, the head of Lilly’s cardiometabolic health division. “The idea that you can get 27 pounds of weight loss from a single pill and also get really encouraging effects on other important biomarkers, things like blood pressure, lipids, inflammatory biomarkers and fasting glucose — those are a lot of the things that [doctors] are really managing when they think about preventative care.”

Custer’s message didn’t resonate with Wall Street investors, however. Leerink Partners analyst David Risinger slashed his 2030 forecast for orforglipron from $22 billion to $14 billion, writing in a note to clients that the lower-than-expected weight loss along with a higher discontinuation rate due to adverse events — 10.3% at the highest dose, versus 2.6% for placebo recipients — could limit its use.

Risinger also downgraded his rating for Lilly shares from “outperform” to “market perform,” noting the growing competition among obesity drug developers, Novo likely cutting Wegovy’s price and pushback from insurers, which could limit market growth to those willing to pay cash.