Eli Lilly’s tirzepatide, the in-demand drug sold as Zepbound for weight loss, has for the first time been shown in late-stage testing to provide a cardiovascular benefit, too.

Summary results from a Phase 3 study showed that treatment with tirzepatide reduced the risk of death or serious complications from a form of heart failure by 38% versus placebo in people with obesity. Some participants in the study, called SUMMIT, also had diabetes.

Tirzepatide treatment led to meaningful improvements on a widely used assessment of heart failure symptoms, the study’s other main goal. Results on secondary endpoints were positive, too, including improvement on a walking test and declines in a measure of inflammation.

The company only reported topline findings. Details will be presented at a medical meeting and published in a peer-reviewed journal. Yet the trial’s success could help Lilly expand use of tirzepatide; the company plans to share data with regulators later this year.

More broadly, the results add to the growing list of use cases for “incretin” drugs, which are approved for diabetes, weight loss and, in the case of Novo Nordisk’s rival drug Wegovy, reducing heart risk. Recent testing has indicated they are beneficial in other health conditions like sleep apnea, chronic kidney disease and a common liver condition called MASH.

For Lilly, the trial helps it keep pace with Novo, which previously found Wegovy to be beneficial in the same type of heart failure. The drug isn’t yet approved for that specific use, though.

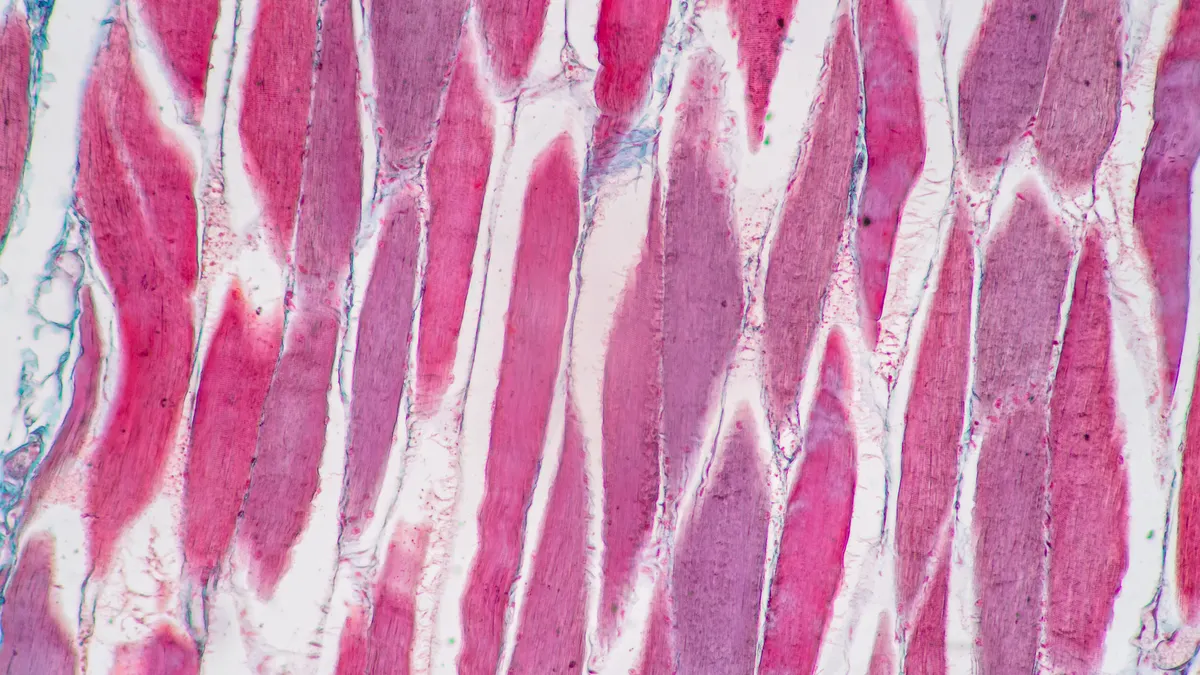

Like Novo, Lilly tested its drug in people with “preserved ejection fraction,” or HFpEF, meaning their hearts can still pump about half of what a healthy heart can.

However, Lilly designed its trial differently, making reduction of heart failure complications a main goal, rather than an exploratory assessment. This could give Lilly more ammunition to convince insurers to cover tirzepatide for this use.

Lilly’s results are “very impressive” compared to other drugs tested previously tested in HFpEF, wrote Leerink Partners analyst David Risinger. Lilly’s Jardiance, a so-called SGLT2 inhibitor that’s recommended for the condition, led to a 21% reduction in the risk of death or hospitalization in a large study. Novartis’ Entresto, another type of drug, was associated with a 13% reduction that narrowly missed statistical significance.

Risinger added that tirzepatide’s impact on symptom scores, as tabulated through a type of questionnaire, also looked “comparable” to Wegovy. Comparing drugs across trials with different designs can be misleading, however.

HFpEF accounts for about half of all cases of heart failure. In the U.S. nearly 60% of those with it are also obese, Jeff Emmick, Lilly’s senior vice president of product development, said in a statement. “Despite a continuing increase in the number of people with both HFpEF and obesity, treatment options remain limited,” he added.

Lilly said tirzepatide’s safety profile was consistent with previous studies. The most common side effects were gastrointestinal, such as diarrhea, nausea, constipation and vomiting, and we generally mild to moderate in severity.

Lilly has other outcomes studies ongoing that are designed to prove whether tirzepatide can prevent heart problems in people with cardiovascular disease. One study in Type 2 diabetics should produce results next year, while another in people with obesity is expected to read out in 2027.

Last year, Wegovy succeeded in an outcomes trial in people with cardiovascular disease who also have obesity or are overweight. The FDA has since broadened the drug’s label, which has given Novo an edge with insurers.