Dive Brief:

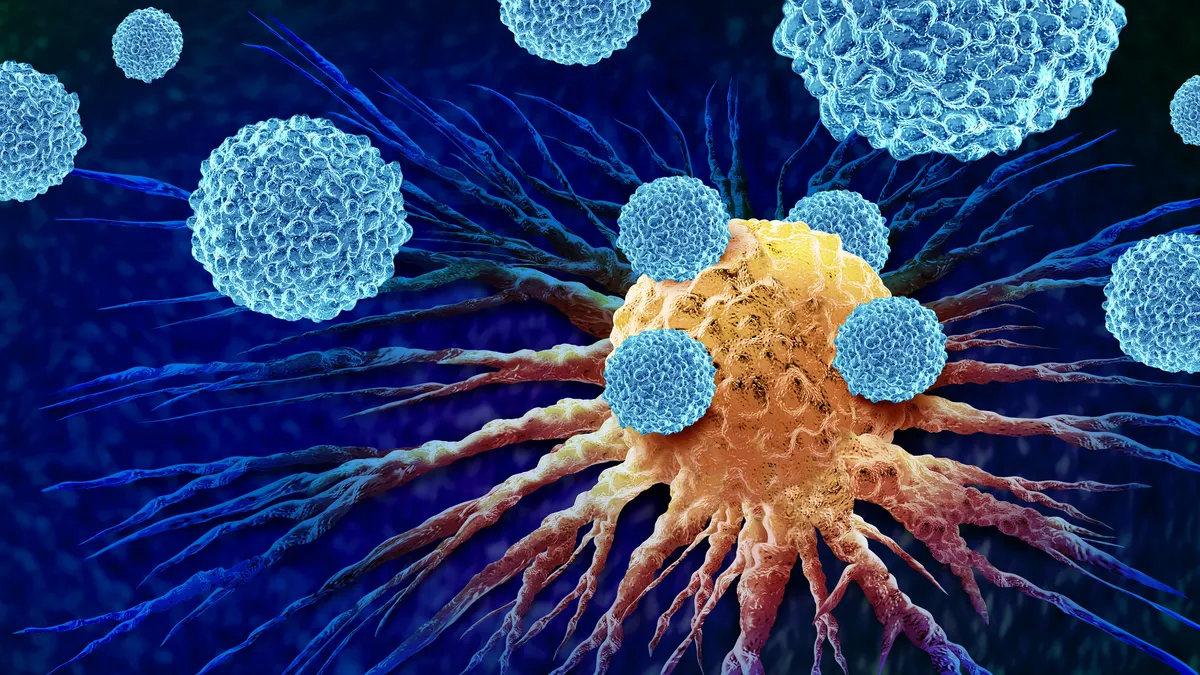

- Merck & Co.’s drug Keytruda failed to help people with cancer in two clinical trials, both using the immunotherapy as an add-on to other types of treatment for early-stage lung and skin cancer, the comapny said Thursday.

- Both trials were stopped early following the recommendation of independent data analysts, who said the addition of Keytruda to standard treatments didn’t appear likely to improve survival for study volunteers.

- The study setbacks are a blow to Merck’s plans to further expand Keytruda’s use ahead of an expected patent expiration in 2028. The drugmaker has spent $46 billion developing Keytruda in more than a decade and plans to spend $20 billion more by 2030, CEO Robert Davis said at this year’s American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting.

Dive Insight:

Keytruda has been Merck’s can’t-miss drug, rapidly becoming one of the best-selling pharmaceutical products of all time with $14 billion in sales in the first six months of 2024 alone. Skin cancer was its first approval and lung cancer has driven a large part of its growth, although it has gained approval in well over a dozen types of cancer.

In recent years, however, its expansion into new indications has slowed as clinical trial results have been less positive. Merck ended 2023 with failures of three Keytruda combination trials, including a coformulation with a new type of immunotherapy. The negative results followed a slow start to 2023, with two combination trials failing to help patients with lung and skin cancer.

The latest trials were in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer and a type of skin cancer called cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. In lung cancer, Merck tested Keytruda and radiation therapy in people whose disease hadn’t spread outside their lungs or had spread only to lymph nodes near the lung, and included people who couldn’t have surgery or refused it.

When compared with people getting radiotherapy plus a placebo, the Keytruda combination didn’t appear to delay relapse, progression or improve overall survival at a preplanned interim data analysis, according to trial monitors. Because Keytruda was associated with more side effects, including adverse events that led to death, the decision was made to terminate the study, Merck said.

In the skin cancer study, Merck tested Keytruda in people following surgery and radiation to determine if it could delay recurrence when compared to a placebo. Again, at a preplanned data analysis, Keytruda didn’t appear statistically likely to improve recurrence-free survival.

Although testing overall survival wasn’t part of the formal data analysis at this interim check, Merck said the signs didn’t appear to favor Keytruda for that secondary study goal.