The Food and Drug Administration on Thursday approved a new medicine for breast cancer, clearing Eli Lilly’s Inluriyo for people with a specific genetic mutation.

Previously known as imlunestrant, the drug has been cleared for use in a subgroup of adults whose metastatic, estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer has progressed after at least one hormone therapy. The approval makes the treatment available specifically to people who fit that criteria and have mutations to a gene called ESR1 — an alteration Lilly believes to occur in about half of people with that form of the disease either during, or after, exposure to hormone therapy.

The clearance was based on results published in the New England Journal of Medicine last year. Those findings, from a study called EMBER-3, showed that Inluriyo helped reduced the risk of disease progression or death among those with ESR1 mutations by 38% when compared to standard hormone-suppressing therapies. Inluriyo delayed tumor progression by a median of 5.5 months, or close to 2 months longer than those on typical drugs.

The majority of side effects associated with treatment were judged to be “low grade,” including lower hemoglobin and white blood cell counts, pain, fatigue, diarrhea and other adverse events that led 4.6% of patients to stop treatment. Some 10% of patients had treatment interrupted because of side effects, Lilly said. The FDA’s prescribing information also includes a warning for potentially harmful effects on a developing fetus.

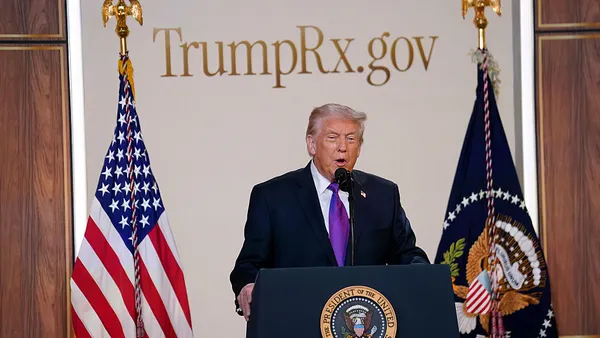

A 28-day supply of Inluriyo has a list price of $22,500 per patient, according to a company spokesperson.

The clearance marks the latest advance for a new group of oral estrogen-degrading drugs known as “SERDs.” These drugs aim to supplant the decades-old therapy fulvestrant, an injectable medicine that’s been a mainstay of breast cancer care. The first, Menarini Group’s Orserdu, was approved in 2023. Inluriyo now joins it, while multiple others from Roche, AstraZeneca and a partnership between Arvinas and Pfizer are close behind.

In a statement, Jacob Van Naarden, the executive vice president and head of Lilly’s oncology division, noted how the approval represents an “important step toward advancing innovative, all-oral treatment approaches” in breast cancer. Komal Jhaveri, a study investigator and clinical director of early drug development at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center added that ESR1 mutations often contribute to treatment resistance, making Inluriyo a “meaningful alternative treatment option.”

Yet it’s unclear how big of an impact Inluriyo and other drugs like it will have on cancer care. At the American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting earlier this year, some doctors interviewed by BioPharma Dive cited some of the “unknowns” in the existing oral SERD results. The drugs also haven’t proven clearly effective in people without ESR1 mutations. Arvinas and Pfizer, for instance, whose competing medicine is under review for a similar population, recently decided to out-license their therapy because of the smaller-than-envisioned market it’ll command.

Lilly could add to its drug’s sales potential, though. The company is studying Inluriyo in an “adjuvant” therapy in early breast cancer, where its goal is to prevent relapses. Initial results could come in 2027, according to a federal database.