The mass layoffs that swept the U.S. health department this month were chaotic and stressful for employees. They may also have been illegal, according to lawyers and federal employment experts.

Healthcare Dive spoke to more than a dozen current and former employees at the Department of Health and Human Services, all of whom shared aspects of the reduction-in-force that don’t match how the process is typically done. The employees were granted anonymity so they could speak without fear of retribution.

Entire offices were closed, including some mandated by law, while termination letters sent to staff contained incorrect information. There were also discrepancies in how HHS determined which employees would be let go, and a general lack of transparency with department heads and employee unions.

Several legal experts agree that some of those issues could be grounds for a lawsuit. Unions and employment law firms are taking notice and reaching out to impacted employees to collect information.

Last Tuesday, a virtual town hall for HHS staff run by Gilbert Employment Law quickly became so crowded that Zoom started bouncing attendees due to capacity constraints. Another firm, Federal Practice Group, told Healthcare Dive it plans to appeal the layoffs with a board that protects government employees from illegal terminations.

Meanwhile, the National Treasury Employees Union, which represents HHS workers in several agencies, has filed an institutional grievance — setting off an internal complaint process that could wind up in front of an arbiter, according to an email to members shared with Healthcare Dive.

Two weeks after HHS started sending out reduction-in-force, or RIF, notices to employees, it’s still not exactly clear how the layoffs were conducted, who’s in charge and how the 10,000 or so affected HHS workers were targeted.

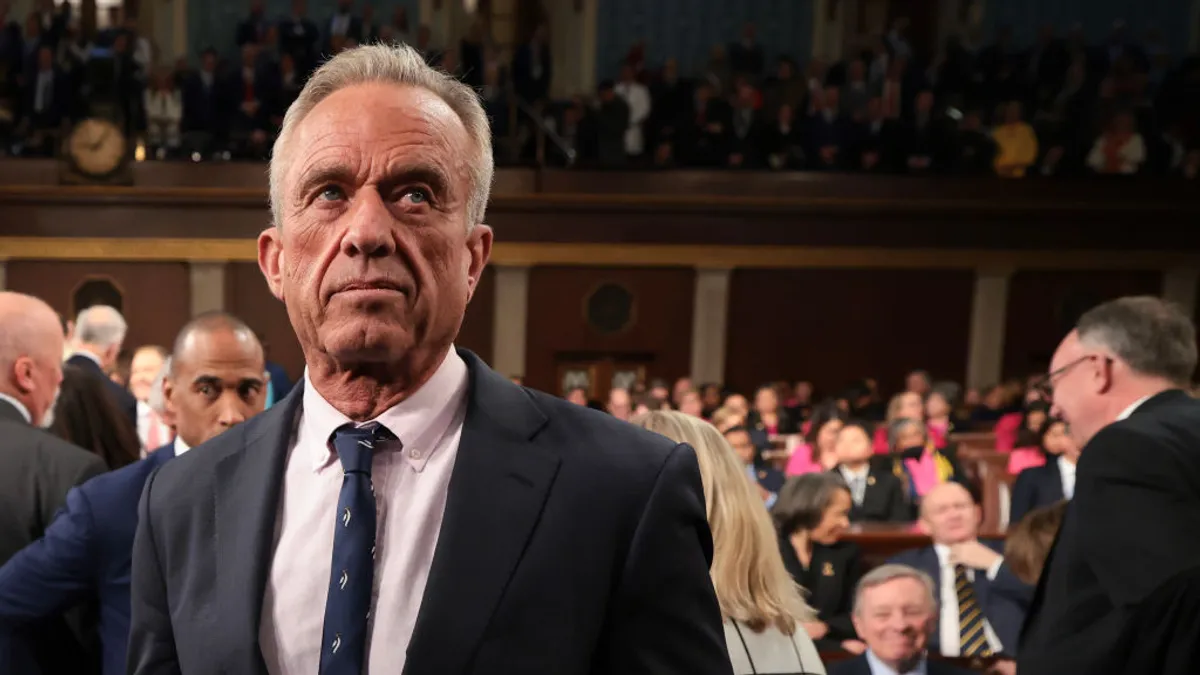

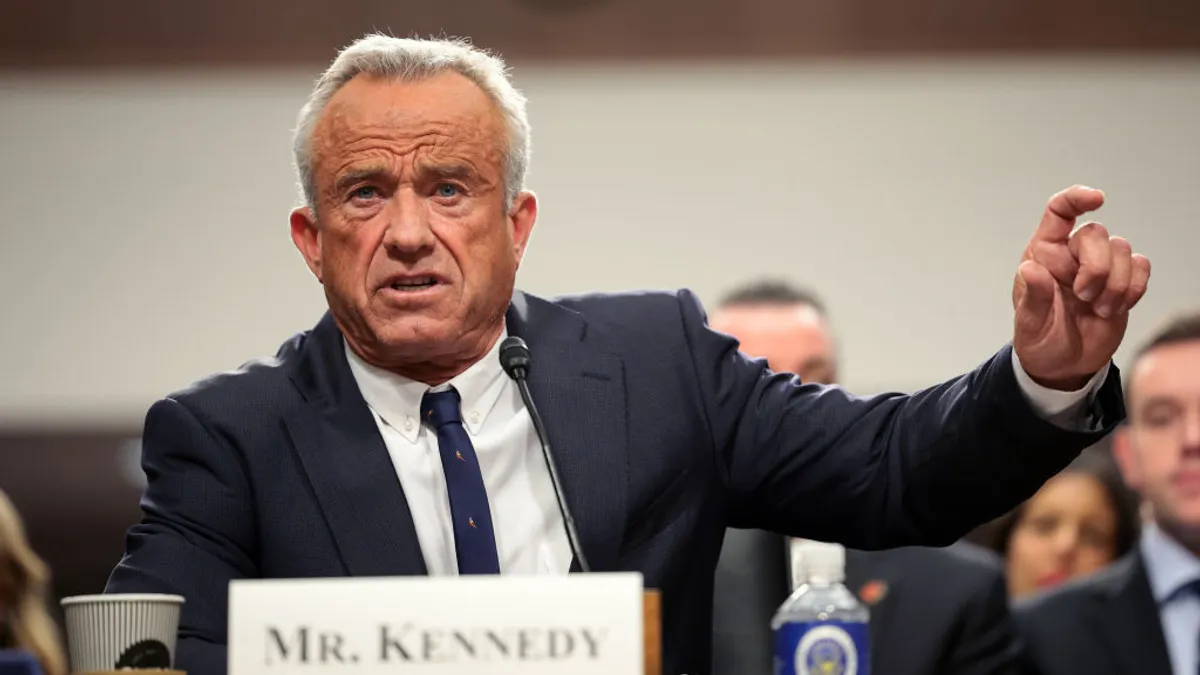

The RIF, which trims the federal workforce by about 25%, has been characterized by confusion from the highest ranks of leadership to the lowest-level employees. Even HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. acknowledged he was unaware of the full scale of the cuts, saying recently in an interview with CBS News that as many as 20% of affected employees may need to be reinstated — a plan other HHS officials shot down.

“This has been done so sloppily and so carelessly,” said one longtime employee at the National Institutes of Health, who was not affected by the RIF. “It’s just staggering to me, the incompetence of this.”

Legal questions

Generally in a government RIF, agency officials identify an area they want to trim, whether that’s a specific geography or office. Those defined parameters are called a “competitive area.” The agency can also specify which types of jobs will be affected by the RIF before determining how many people, or what percentage of a competitive area, they want to let go.

Then, the agency assigns all employees within that competitive area a score based on the date they started at the agency, their veteran status, performance record and whether they’re a tenured or a probationary employee.

Employees are dismissed or retained based on their position in that ranking, which is called a “retention register.” Agencies also can offer reassignments to a lower level post to keep valuable employees onboard while still cutting their position, in a process called “bump and retreat.”

Government reductions are essentially “a game of musical chairs” where “the RIF decides who gets the chair,” said Ron Sanders, a longtime government official who oversaw RIFs for the Department of Defense in the 1990s.

The entire process can take months and is highly manual if followed to the letter. Not so this month at HHS, where instead of carefully trimming employees, officials have elected to shut down entire offices — a strategy that allows them to move faster and get around the ranking requirements altogether, according to experts.

That’s highly irregular but may not be illegal, depending how the HHS defined competitive areas, Sanders said. If the HHS defined the competitive area as a single office and closed the entire thing, they’re not required to do the ranking.

However, Healthcare Dive has identified at least four separate offices where employees received RIF letters designating their entire office as their competitive area and saying the entire area was being separated — yet not everyone in the office was let go.

Healthcare Dive is not disclosing the exact offices to protect the identity of sources. However, they span multiple HHS divisions at the NIH, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Administration for Children and Families.

“I assume they just haven’t gotten to us yet,” said an NIH employee in one such office. “If they cut whole offices, they can do this fast-tracked thing and just get rid of everyone. But they can’t keep some people and not others.”

Tamara Slater, a shareholder at employment law firm Alan Lescht and Associates, agreed this looks like a violation of the law.

“I do think that there are a fair number of pieces, while looking over the RIF notices, that don’t seem to have been properly followed,” Slater said.

It appears HHS is trying to circumvent RIF regulations by separating entire competitive areas — without actually separating everyone in a competitive area, she noted.

“I think that’s what they’re trying to do, and I think there will be legal challenges to it,” Slater said.

RIF notices sent to affected employees from Tom Nagy, HHS’ chief human capital officer, said that retention registers were prepared to conduct the RIF.

Yet one former employee with the ACF said it appears unlikely the department actually went through with the ranking process based on who was let go and who wasn’t in their office.

“I have more seniority than one of my direct reports who wasn’t RIFed, and who would have been if they had done this properly,” they said.

A spokesperson for HHS did not respond to multiple requests for comment on how the RIF was carried out.

The government does have some leeway in how it undergoes a RIF, according to lawyers, which creates some uncertainty as to whether a court would find HHS’ actions illegal.

Competitive areas could be incorrect on RIF notices but correct in the HHS’ internal systems that oversaw the RIF, meaning the RIF was performed correctly even if employees don’t know it.

For example, if the competitive areas zeroed in on a specific region or job type in addition to an office, the department could have laid those particular employees off without ranking them against their peers.

“All other things being equal, an agency can define a RIF competitive area very, very narrowly,” Sanders said. “You can have coworkers — some in one category, some in another — but their desks are right next to each other. Some might receive RIF notices and others may not.”

As it stands, however, “I think a lawsuit has a decent shot,” said Tom Spiggle, the founder of Spiggle Law Firm, which works on wrongful termination cases, including for government employees. “It sounds like this has not been done according to the law.”

Unions, law firms take action

Other elements of the RIF are also problematic, including inaccurate information in termination letters, according to sources and experts. In some cases, employees received RIF notices with the wrong office name on them or with incorrect performance scores.

Such errors are probably not illegal on their own, but can have negative effects on specific employees by impacting their positioning on a retention register or the severance they’re entitled to, according to employment lawyers.

People with issues on their paperwork should notify HR and plan to appeal their case to the Merit Systems Protection Board, a quasi-judicial agency in the executive branch that oversees federal employment issues, said Robert Hinckley Jr., a managing shareholder with law firm Buchalter.

There are some problems with that approach, though. Many of HHS’ HR staff were also let go in the layoffs, as were staff in Equal Employment Opportunity Commission offices, which will lead to backlogs in corrections requests and prevent employees from filing concerns about discrimination, according to sources.

Similar issues affect the MSPB, which was operating with only one of its usual three board members earlier this year after one member’s term lapsed and President Donald Trump removed a Democratic appointee.

That appointee, Cathy Harris, was reinstated by a district court before the Supreme Court temporarily upheld her dismissal. That leadership turmoil, combined with a surge of other federal employees trying to appeal the administration’s mass firings, will probably create a bottleneck for cases, employment lawyers said.

In the near term, that gives employees little recourse for complaints about how the RIFs were carried out.

Lawsuits could fill that gap. At least two Washington, D.C.-area law firms are communicating with affected HHS employees and exploring the possibility of a class-action lawsuit, including Gilbert Employment Law, the firm that held last Tuesday’s town hall, and Federal Practice Group.

“We have been contacted by hundreds and hundreds of HHS employees at multiple subagencies issued RIF notices with errors ranging from odd definitions of their competitive area to incorrect performance ratings, veterans’ status, and service computation dates,” Debra D’Agostino, the founding partner of FPG, told Healthcare Dive over email. “We are planning to file class action MSPB appeals on their behalf.”

FPG anticipates success because nearly all of the RIF notices contain errors and it doesn’t seem that any HHS HR offices created retention registers as required by law, according to D’Agostino.

“Instead, it appears that, likely led by [the Department of Government Efficiency], someone took an organization chart and started crossing off certain offices, divisions, branches, etc., and then generated RIF notices for the employees in those offices pulling from an old database, which is why they are riddled with inaccuracies,” she said.

HHS unions also allege the department’s actions violate collective bargaining agreements for how RIFs should be handled.

The NTEU has filed an institutional grievance against HHS for violating RIF procedures and breaking its contract by not giving the union proper notice, the union told its members Wednesday. NTEU covers workers in the Food and Drug Administration, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the ACF and other agencies.

The challenge, which could end up before an independent arbiter, asks HHS to reinstate impacted employees.

However, Trump in March issued an executive order eliminating collective bargaining rights for hundreds of thousands of federal employees, including within HHS. The order, which unions have challenged in court, was made in advance of the layoffs and could give the administration legal cover for breaking its contract with HHS unions.

“Failing to notify the unions is a big problem. And I suspect that’s one of numerous reasons why that executive order on March 27 was issued, saying that collective bargaining agreements were not going to be applicable to specific listed agencies — including HHS,” Slater said.

Despite several lawyers agreeing legal challenges have a good chance, one staffer with the Food and Drug Administration who was not affected by the cuts said they expect the outcome would likely be the same as other occasions when the Trump administration has moved ahead with an aggressive interpretation of executive power.

“No one listens to the courts anyways,” they said. “It’s dire times.”