A regimen combining a new experimental Roche medicine with an older drug lowered the risk of disease progression or death by nearly two thirds in people with a certain type of breast tumor, according to study data revealed Saturday.

Roche disclosed last month that the closely watched Phase 3 study had succeeded, but presented details for the first time on Saturday at the European Society for Medical Oncology meeting in Berlin. The data, should it lead to a regulatory approval, could help distinguish the company's medicine from others like it. These drugs — collectively known as selective estrogen receptor degraders, or SERDs — are newer, oral versions of a decades-old treatment widely used against breast cancer. Two of them, Eli Lilly’s Inluriyo and Menarini Group’s Orserdu, are already available.

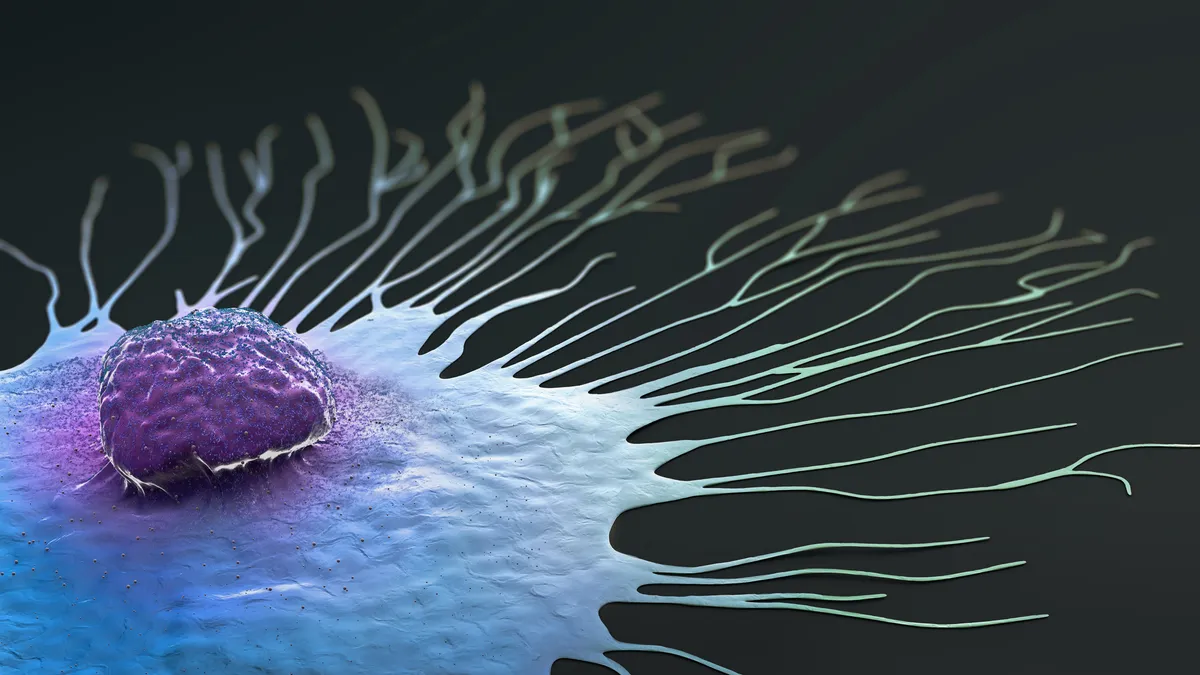

Roche's giredestrant and its peers have been evaluated against "ER-positive, HER2-negative" breast cancer, the most common form of the disease. That form is first treated with hormone drugs and a type of targeted therapy called a CDK4/6 inhibitor. Many patients progress, though, and afterwards, the options are more limited.

Over the last two years, Orserdu and Inluriyo have increased those options. In testing, they’ve proven effective in people whose ER-positive, HER2-negative tumors progress and have a mutations to a gene called ESR1 — an alteration that occurs during or after exposure to hormone therapy. Orserdu, for example, was associated with a 45% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death compared to hormone therapy, while Inluriyo posted a 38% risk reduction.

Roche is the latest to read out results. In its trial, named evERA, Roche combined giredestrant with “everolimus,” a drug sold under the brand name Afinitor and used in second-line, ER-positive disease. The trial tested that combination against older hormone treatments and everolimus, measuring its ability to hold disease in check among those with ESR1 mutations as well as the overall study population.

The results presented Saturday show the giredestrant combination reduced the risk of progression in the ESR1-positive population by 62% and in the broader group by 44%. An “exploratory” analysis of only those without ESR1 mutations — which wasn’t as statistically robust as the other findings — showed no significant difference in the risk of disease progression between people who got giredestrant or other hormone therapies, according to lead study investigator Erica Mayer, an oncologist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

However, Mayer noted the analysis did show signs of a benefit on response rates, the length of those responses, and patient survival. The “totality of the data supports the improvement seen in the [broad] population” in the trial, she said.

“I think the majority of medical oncologists feel that the optimal treatment after a CDK [inhibitor] is endocrine therapy plus a targeted partner,” Mayer said. “I’d be very excited to use this regimen in clinic with patients.”

While trials are often difficult to directly compare, Inluriyo didn’t delay progression in the broad group of ESR1-positive and negative enrollees in the pivotal study underlying its approval. Orserdu did, reducing the risk of progression by 30%, but still wasn’t cleared for non-ESR1 patients because the benefit was “primarily attributed to results from patients in the ESR1-[positive] subgroup,” FDA reviewers wrote.

Inluriyo hasn’t been on the market long enough for Lilly to report quarterly sales. And as a private company, Menarin doesn’t publicly report earnings. But a drug royalty company called DRI Healthcare has acquired twice pieces of Orserdu sales, first buying into a “mid-single digit” percentage of royalties and then a “low to high single-digit” royalty stream. Last year, the first piece generated $28.4 million for DRI and the second earned $37.1 million.