In the notoriously expensive business of drug development, SiteOne Therapeutics made do with little. The biotechnology startup formed in 2010, aiming to create new, non-addictive pain relievers at a time when overdoses involving opioids were killing more than 20,000 people in the U.S. each year.

Yet the dire need for safer medications didn’t resonate with most investors. To them, pain was too risky. Scientists knew the general outline of how it worked: a cut, scald, break, pinch, slam or zap would alert special proteins and chemicals, which, like sentries, relay pain signals through the body. But the finer details of this process were — and, in many cases, still are — fuzzy, like how people who suffer the same injuries can report very different pain experiences.

This uncertainty meant SiteOne had to, for most of its life, rely on small grants to stay afloat. “There was certainly a difficult period,” CEO John Mulcahy said late last year. “Pain was out of favor, so it was difficult to raise capital around these assets.”

That period now appears over. In the last eight months, SiteOne not only closed a $100 million fundraising round led by Novo Holdings, the controlling stakeholder of Ozempic-maker Novo Nordisk, but also agreed to sell to Eli Lilly in a deal that could be worth up to $1 billion.

The newfound interest and investment can be attributed, in good part, to Vertex Pharmaceuticals, which has led the charge investigating a group of tube-shaped, pain-regulating proteins called sodium ion channels. After a quarter century of meticulous, onerous work, Vertex’s labs finally crafted a channel-blocking molecule the company viewed as safe, effective and precise enough to help address the opioid epidemic.

In January, the Food and Drug Administration approved this molecule, known commercially as Journavx, as a treatment for the sharp, short-lived “acute” pain felt after an accident or surgery. Ken Harrison, a senior partner at Novo Holdings, said a core reason his firm decided to back SiteOne was that Vertex had established these drugs can be successfully studied and brought to market.

While Journavx has so far proven remarkably safe and absent of addictive properties, doctors remain torn about how useful it will ultimately be for patients. At its best, the drug looks to be only as potent as a weak opioid. At least 5,800 Journavx prescriptions were written during the third week of June; millions more will need to come for it to meet Wall Street’s blockbuster forecasts.

Still, TD Cowen analysts recently described the drug’s approval as a “watershed moment that could pave the way for a new era of non-opioid pain treatments.” Indeed, SiteOne and at least 10 other developers want to follow in Vertex’s footsteps with their own medicines that stopper either the “NaV1.8” sodium ion channel, as Journavx does, or a close cousin, “NaV1.7.”

What are sodium channel inhibitors, and how do they work?

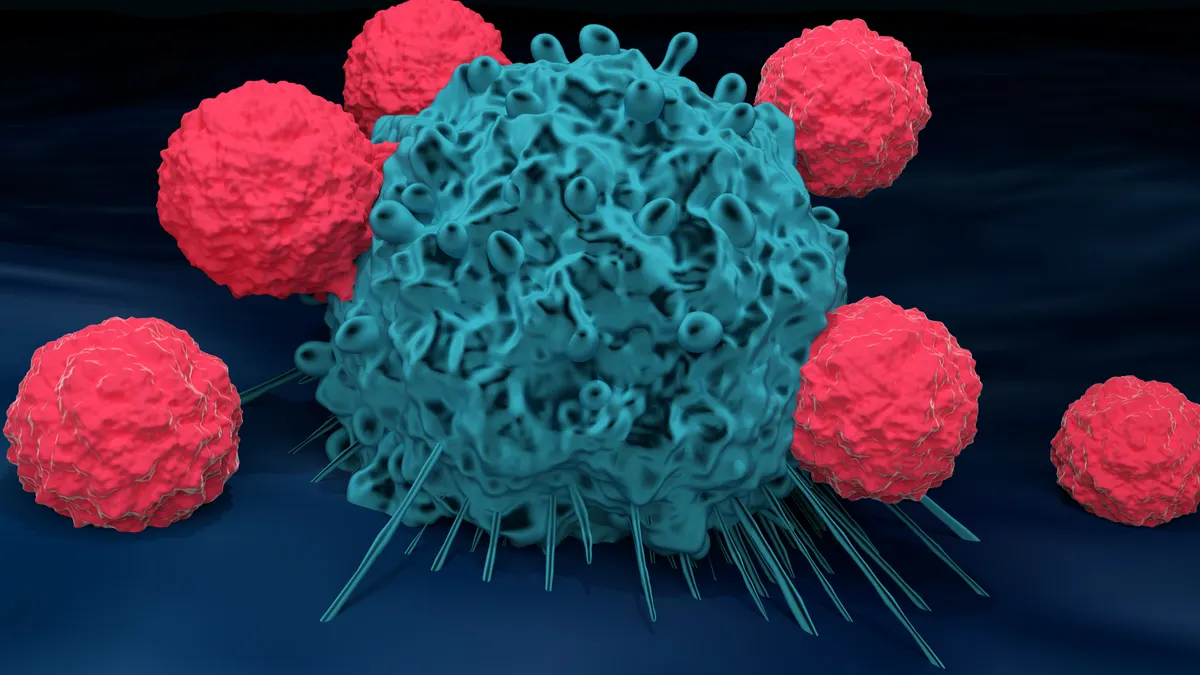

Found in the outermost layers of many cells, these proteins function like faucets for charged sodium particles. They open in response to various stimuli — a bright light switching on, a bite of a salty food, a handful of ice from the freezer — at which point ions flood into the cell. This rush creates an electrical pulse that travels through the nervous system and to the brain, where it's used as information to determine how the body should feel and react.

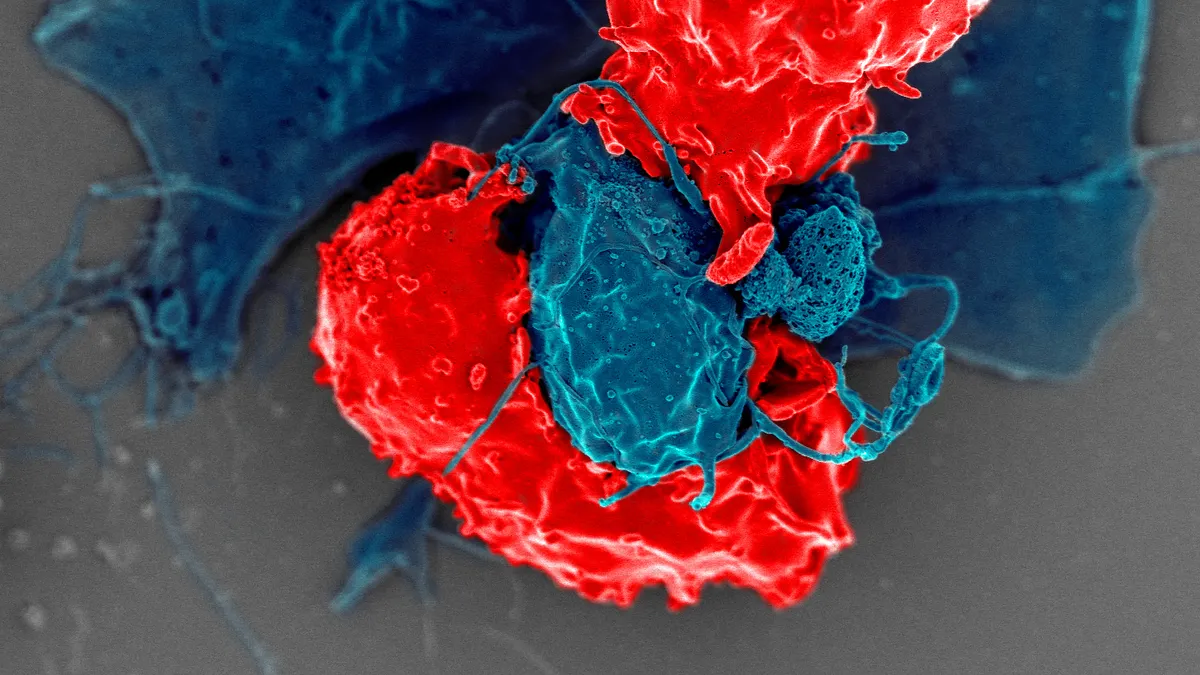

Of the nine known types of sodium ion channels, three are primarily found in the peripheral nervous system, where they play key roles in pain signaling. The signaling process resembles a line of dominoes. At the start is the root of the pain, at the end the brain. By blocking these channels, scientists are effectively removing a couple of the earliest tiles so they can’t continue the cascade.

“You’re stopping the pain as close as you can to the source,” and leaving “other modalities of sensory signaling intact,” explained Stephen Waxman, a neurology professor at the Yale School of Medicine who’s made significant discoveries about the role ion channels play in pain, on a 2023 podcast run by The New England Journal of Medicine.

For drugmakers, NaV1.7 and NaV1.8 have emerged as the two most popular pain targets. One reason is their location. Being on the outer edge of the nervous system, rather than thoroughly embedded in organs like the heart or brain, reduces the risk that channel-blocking drugs will disrupt other vital body functions.

These proteins also work in different ways, offering researchers a shot at treating a variety of pain types. NaV1.7 acts like a light switch, abruptly turning the pain signal on and off, while NaV1.8 is more akin to a dimmer. SiteOne’s Mulcahy has said NaV1.8 could therefore be a more desirable target for chronic pain management, since the goal there usually is not to shut pain off, but to dial it back down to “normal.”

Designing medicines that bind to a specific sodium channel remains exceptionally challenging, as the subtypes all share very similar structures. Additionally, the proteins move extremely fast — opening and closing in milliseconds — and are exposed to relatively large electrical fields. Only in the last 15 or so years, with the creation of new tools, have drugmakers been able to adequately study and precisely drug ion channels.

What are the advantages over other drugs for pain?

Scientists believe that, by avoiding the central nervous system, sodium channel blockers can alleviate pain without eliciting the side effects or addictive risks posed by opioids. The late-stage studies that led to Journavx’s approval support this theory.

Together, the two trials recruited more than 2,000 people who had just undergone either a “tummy tuck” surgery or a bunion removal. Participants received either Vertex’s drug, a placebo, or a combination of Tylenol and a commonly prescribed opioid that served as an “active comparator.” Investigators found lower rates of nausea, dizziness and headache among those given Journavx than in the other groups.

Journavx was generally safe and well-tolerated, according to Vertex, and nearly all of the adverse events seen in these studies were mild to moderate in severity. Drug-treated patients did, however, show higher rates of itchiness, rash and muscle spasms compared to their placebo-treated counterparts.

As for its effectiveness, Journavx proved significantly better than the placebo at alleviating acute pain. Both trials measured this with a 0-to-10 scale wherein patients rate their pain intensity at a series of time intervals over two days.

Notably, the drug was not more effective than the active comparator regimen. That’s raised debate about its utility in a setting like acute pain, where both patients and healthcare providers are typically looking for a powerful, quick-acting medication. While Vertex leadership has maintained this finding won’t deter doctors from prescribing Journavx, some pain experts have described the pill’s effects as modest. Richard Vaglienti, medical director of the Center for Integrative Pain Management at West Virginia University, even classified the results as “glaring.”

That could leave the door open for other developers to compete — even those working outside the field of sodium ion channels. In May, Pittsburgh-based Viatris reported positive results from late-stage studies evaluating a reformulated version of an old medication, an “NSAID” called meloxicam, in people who had bunion removal or hernia repair surgeries. Viatris said its drug didn’t just beat a placebo at providing acute pain relief, an after-the-fact analysis found it also offered “significantly superior pain control” to tramadol, an opioid less potent than the one used in Vertex’s studies.

Following this release, Brian Skorney, an analyst at the investment firm Baird, noted how Viatris’ data “highlight a number of concerns we have with Journavx’s profile, in particular, onset of action, a critical factor for post-operative pain.”

The results, Skorney argued, make Journavx “look like an inferior option” compared to a “pretty old” drug. “If NSAID’s don’t have the highest efficacy, as Vertex is fond of saying, what does that say about Journavx?” he wrote.

Select companies developing sodium channel inhibitors for pain

| Company | Program name | Target / type of pain | Stage of development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vertex Pharmaceuticals | suzetrigine | NaV1.8 / acute and chronic | Approved / Phase 3 |

| Latigo Biotherapeutics | LTG001 | NaV1.8 / acute | Phase 2 |

| Dogwood Therapeutics | Halneuron | NaV1.7 / neuropathic | Phase 2 |

| Newron Pharmaceuticals | ralfinamide | NaV1.7 / neuropathic | Prior testing completed |

| SiteOne Therapeutics | STC-004 | NaV1.8 / acute and chronic | Phase 2 ready |

| Channel Therapeutics* | CT8464, CC2000, CC3000 | NaV1.7 / chronic and eye | Phase 2 ready / Phase 1 |

| Sangamo Therapeutics | ST-503 | NaV1.7 / chronic | Phase 1 |

| Xenon Pharmaceuticals | Undisclosed | NaV1.7 / undisclosed | Preclinical |

| Navega Therapeutics | NT-Z001 | NaV1.7 / chronic | Preclinical |

| Praxis Precision Medicines | vormatrigine | NaV1.7 and NaV1.8** | Undisclosed |

| RaQualia Pharma / Himitsu Pharmaceutical | RQ-00350215 | Undisclosed / chronic** | Undisclosed |

*Channel Therapeutics is being merged into Pelthos Therapeutics via a deal expected to close in summer 2025. **Specific sodium channel target and/or type of pain not disclosed. SOURCE: Companies, clinicaltrials.gov

Which companies are developing NaV1.7 and NaV1.8 inhibitors?

The majority of developers researching sodium ion channels for pain are small biotechs.

One, Dogwood Therapeutics, formed late last year through the reverse merger of Wex Pharmaceuticals and Virios Therapeutics. It had 12 full-time employees at the end of December. Another, Channel Therapeutics, had four, and is now in the process of combining with a subsidiary of drug commercialization specialist Ligand Pharmaceuticals.

Such deals could suggest that, while this area is receiving more attention, building a company around it remains challenging and may require less conventional methods for raising money at a time when investors are viewing biotech more skeptically.

Other players include Praxis Precision Medicines, Newron Pharmaceuticals, RaQualia Pharma and Xenon Pharmaceuticals. Two more, Sangamo Therapeutics and privately held Navega Therapeutics, are taking a genetic approach, with therapies built to suppress the gene that encodes for NaV1.7 proteins.

Latigo Biotherapeutics is further ahead, and like SiteOne touts a drug aimed at NaV1.8 in mid-stage testing. That drug, LTG001, is being evaluated in acute pain following a tummy tuck, bunionectomy or wisdom teeth removal.

Latigo is backed by prominent life sciences investors such as Westlake Village BioPartners, 5AM Ventures and Alexandria Venture Investments, and in March announced the closing of a $150 million funding round that CEO Nima Farzan said should keep the company going at least until it has late-stage data for LTG001.

Vertex and Eli Lilly, with its pending purchase of SiteOne, currently appear to be the sole big pharmaceutical firms in this space, though others have shown interest. AbbVie had “ABBV-318,” an oral molecule designed to inhibit both NaV1.7 and NaV1.8, but no longer lists the drug in its pipeline. Scientific American reported last year how Merck & Co.’s patent activity also suggests it may be stealthily exploring ion channels for pain.

A Merck spokesperson said the company is “committed to neuroscience research,” including chronic and acute pain. “At this time, it’s too early to share information related to sodium ion channel inhibitors, but we will continue to collaborate with scientists and investigators worldwide to advance innovation and find solutions that may address complex and debilitating neurological diseases.”

At Vertex, company leaders are trying to expand Journavx’s approval beyond acute pain and into chronic, though testing has thus far delivered mixed results. Vertex is working on a series of other, small molecule pain drugs, too, including a “next-generation” NaV1.8 inhibitor named VX-993.

The investment bank Stifel models Journavx sales reaching $1.1 billion in 2030 and $3.6 billion in 2038. The average analyst estimate on Wall Street, according to Stifel, is that sales of the drug will hit nearly $2 billion by the end of this decade.

What is the status of these companies’ research?

Vertex is now enrolling a Phase 3 study to evaluate Journavx as a treatment for the chronic nerve pain experienced by some patients with diabetes. Simultaneously, it’s running a smaller study of VX-993 in the same setting.

The assets from Latigo, Newron and Dogwood have either entered or gone through mid-stage trials. A roughly 250-participant study is exploring Latigo’s LTG001 for wisdom teeth removal pain, with results set to arrive sometime in the next couple months. The active ingredient in Dogwood’s Halneuron is actually the neurotoxin found in pufferfish. Investigators are now hoping to enroll about 200 patients in an experiment that will assess the drug as a treatment of chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain.

Meanwhile, a federal database of clinical trials shows the most recent listings for Newron’s ralfinamide were last updated in 2009 and 2017. The Italy-based company didn’t respond to requests for more recent information about the program.

SiteOne hopes to “rapidly advance” into Phase 2 testing the medicine that caught Lilly’s eye and encouraged it to pursue an acquisition. Like Journavx, this “STC-004” therapy is designed to obstruct NaV1.8.

Mark Mintun, group vice president of Lilly’s neuroscience research and development, in May said that the company is “eager to continue” advancing STC-004. “Innovation in pain management is critical to address the unmet needs of millions of patients around the world.”