Cancer patients are living longer than ever. Pain drugmakers haven’t kept up.

1. The patient

Mary Sage lay frozen in place, in such severe pain she couldn’t will herself off the chiropractor’s table.

It was 2015, and Sage, then a 56-year-old program operation analyst at the University of Washington, was desperate for relief from back aches so intense they could make her double over and collapse. The pain was sharp, energetic, searing, as if electricity was ricocheting from her hips to her neck and down again. Before long, it had become debilitating enough that Sage began relying on a large walking stick that made her feel like Moses.

Sage’s primary care doctor thought she might have a kidney issue and recommended drinking more water. Physical therapists wrote it off as arthritis. “All of them were actually correct,” she said, “but the big thing everyone missed was that tumor.”

Doctors finally found her cancer that fall, when the pain had gotten so unbearable Sage decided she needed to go to the emergency room. A two-week hospital stay, punctuated by a bevy of body scans, led to a diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Corrupted white blood cells were crowding the insides of her bones, weakening them like ivy on a brick wall. Later tests would find she had been living with more than a dozen spinal fractures.

Today, Sage is in remission, her disease kept mostly in check by a Bristol Myers Squibb medicine called Pomalyst. She’s part of a larger trend. Thanks to breakthroughs in drug research, cancer patients are on average living longer than ever. But so, too, is their pain. And there, experts are far less sure how to find lasting solutions.

Pain from cancer and cancer treatments presents unique challenges. It manifests in seemingly countless ways. Tumors can smush nerves, corrode bones or carve into organs. Chemotherapy can fry neurons so badly it creates the sensation of pins pricking the skin. And compared to other diseases, the life-threatening nature of cancer can make the associated pain more likely to be put on the backburner. Sage said hers wasn’t adequately addressed until about five years into treatment.

“Cancer pain is a whole different ball game,” said Allyson Beechy, a clinical pharmacy specialist at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute. “It's the most severe pain I've ever seen, and very stubborn.”

Those characteristics have given rise to a major health problem. More than 2 million people in the U.S. alone are diagnosed with cancer each year. Conservative estimates hold that between 20% and 50% experience related pain, though that figure can climb as high as 80% for patients with advanced disease.

Despite the large number of patients and the need for more therapies, drugmakers have mostly shied away from pain altogether, fearing that its complicated biology makes for too risky a research investment. Partially as a result, there isn’t a diverse range of pharmaceutical options for cancer pain beyond what patients might already find in their home medicine cabinets, like Tylenol and Advil, or the type of over-the-counter drugs offered at local pharmacies. Opioids remain the core of many treatment regimens.

This lack of drug choices is aggravated by much broader failures of the healthcare system. Often, cancer patients can’t get ahold of the existing painkillers that would work best for them, either because of shortages, high costs, or hoops set up by insurance companies and pharmacy managers. This can be particularly dangerous when a patient’s pain is so traumatic they can’t handle cancer therapy until it’s alleviated.

Most treatment centers also don’t have sufficient staff dedicated to cancer pain. Doctors don’t expect that to change anytime soon, as relatively few medical programs are training the next generation of specialists.

Collectively, these shortcomings make daily life more harrowing for patients already staring down a deadly disease. Sage takes 32 pills per day: some for her myeloma, some for heart health, some for pain and then some for the constipation those painkillers cause. She describes the fatigue from her cancer and the opioids she requires as overwhelming.

And still, the pain persists. “It’s a constant day of coping with time and management of your body,” she said. “People don't believe you. They’ll say, ‘How can you live in that much pain?’ And I say, ‘Well how can I not? There's no other option.’”

2. The drug hunter

Steven Paul knows, maybe better than anyone, how to navigate the nervous system.

The acclaimed neuroscientist spent the past 15 years building biotechnology companies, two of which achieved rare feats by crafting first-of-their-kind medicines for schizophrenia and postpartum depression. Prior to working with startups, Paul oversaw neuroscience drug development at Eli Lilly. Under his leadership, the company brought to market the prized brain medications Zyprexa and Cymbalta. Each generated around $5 billion in annual sales at its peak.

Pain played a surprising role in the commercial success of Cymbalta, which was initially used for depression. Though developers weren’t very excited by pain, mounting evidence had suggested molecules like Cymbalta also possess analgesic properties. That prompted Lilly to run a series of experiments, which brought about approvals in a few types of chronic pain between 2004 and 2010. Even now, Cymbalta is the go-to agent for chemotherapy-induced nerve pain.

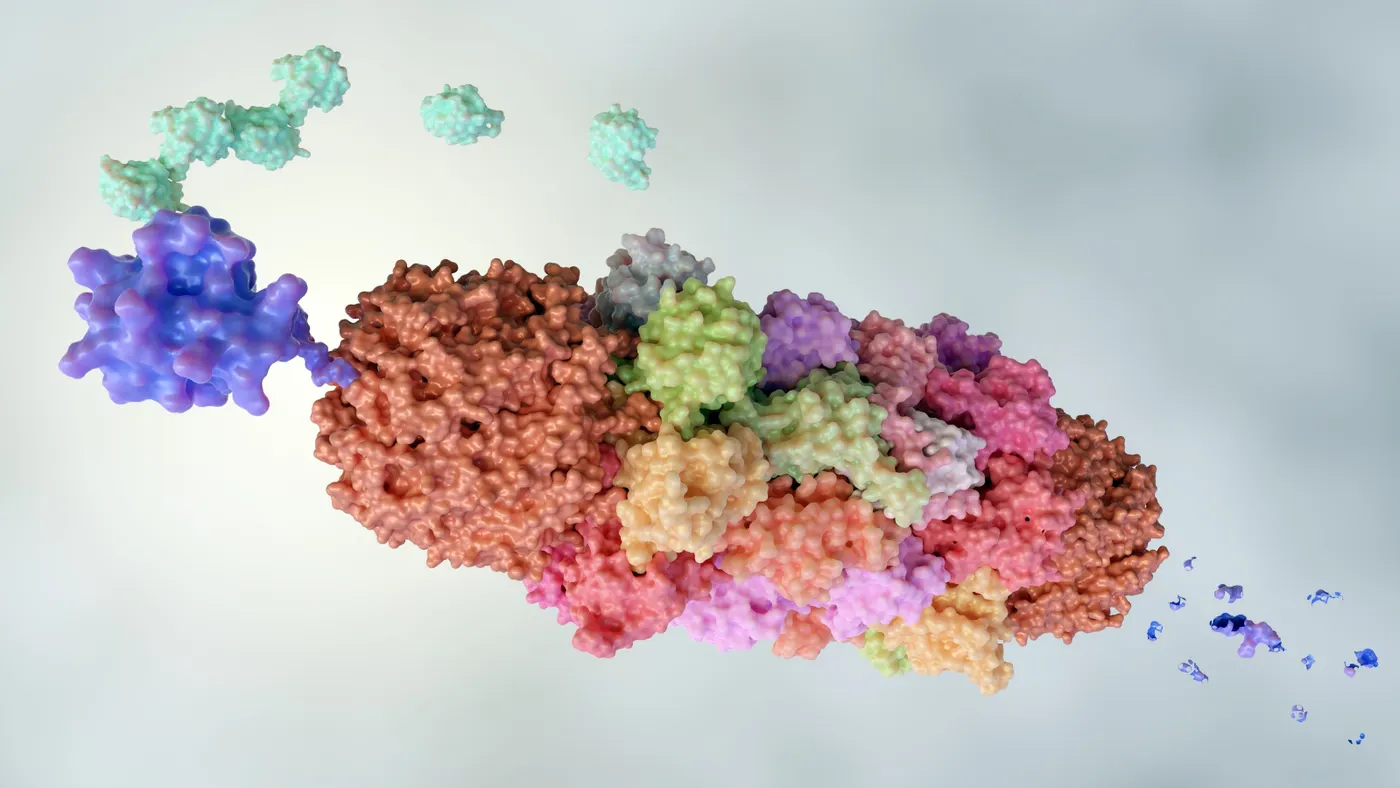

Stories like Lilly’s could have ignited widespread interest in pain — especially since, as Paul recalls, the science was evolving rather quickly around the time Cymbalta first came to market. In fact, researchers had recently made a major discovery: that by inactivating the genes for certain “sodium ion channel” proteins, they could block key pain signals in mice. Maybe the same could be true in humans.

But in the decades since, pain research has moved slower than expected, which may be why most of big pharma still won’t commit to it. While there have been a couple notable strides, like a new class of migraine therapies that emerged in the late 2010s, nothing truly needle-moving has come forward for cancer pain.

That’s triggered palpable frustration from both patients and healthcare providers, some of whom think the drug industry squandered what little energy it did put into pain research by focusing on opioid reformulations instead of new mechanisms.

“They put cheap opioids in a special skin to make them come out slowly, and then charged 10 times more. That’s all they did,” said Billy Huh, a professor in the pain medicine department at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

This year, Journavx, a sodium channel-clogging drug from Vertex Pharmaceuticals, generated some needed optimism by winning a milestone approval as a non-opioid treatment for “acute” pain. At least nine smaller biotechs, as well as Lilly, aim to follow in Vertex’s footsteps with their own pain medicines targeting these proteins. There’s buzz that sodium channel drugs might just resuscitate a dormant field.

“We have better tools, better targets, better biology,” Paul said, but “it's still somewhat early days. A lot will depend on how many clinical trials read out positive or negative. That'll determine people's level of enthusiasm for continuing to invest.”

While hopeful for more advances in Journavx’s mold, doctors don’t see the drug itself as useful for the kind of obstinate pain that cancer causes. Jacob Strand, a palliative care specialist at the Mayo Clinic, noted how Vertex’s studies found Journavx to be better than a placebo, but not more potent than a combination of hydrocodone and acetaminophen — a treatment regimen pretty much all the cancer patients he sees have tried and exhausted already.

Beechy, at Dana Farber, holds a similar opinion. “I have no data that it will be helpful for my patients,” she said.

Her view isn’t all that surprising, as Vertex designed its experiments to show Journavx is useful against the short-lived pain that follows an accident or surgery. Though the company wants to expand the drug’s use into chronic settings, its work there has centered on nerve pain from diabetes or sciatica, not cancer. Close to none of the sodium channel drugmakers coming behind Vertex have programs directed at cancer-related pain.

Such choices exemplify the usual risk-reward assessments that developers make before jumping into a maturing field.

“Would a company solely go after cancer pain? I'm not certain, unless the mechanism of a particular painful condition associated with cancer were clear, clear, clear,” Paul said. “Otherwise, it would probably be a very risky development proposition.”

Opioids further complicate these calculations. Due to their effectiveness at quenching pain, drugs like morphine or oxycodone have set such a high bar that it can deter developers from targeting other brain or nerve pathways.

“The challenge from a commercial perspective is finding something so unequivocally better than a cheap opiate or a cheap nonsteroidal. You're going to have to beat those babies,” Paul said. Any company that can “will be really, really rewarded. And patients will be rewarded too.”

For the time being, opioids stand as the most tried-and-true method of dealing with cancer pain. The dangers this reliance poses are both obvious, in the spectres of addiction and withdrawal, and insidious, like in the creeping fatigue or gut irritation these drugs commonly cause.

3. The advocate

Michael Tuohy was told to get his affairs in order.

He had been dealing with awful back pain, as if a hot knife were twisting into his lumbar. But Tuohy figured that, between being a father of two young kids and a toolmaker who most days stood for hours on a concrete floor, he probably just tweaked a muscle.

Eventually, though, the pain got so insufferable he sought help from an orthopedic doctor, who ordered an MRI. The scan showed a tumor wearing away the base of his spine. He, too, had multiple myeloma, a cancer that usually affects people twice his age. Doctors said Tuohy, at 36, likely had two to three years left to live.

Following that diagnosis in 2000, Tuohy received an exhaustive series of treatments. First low-dose radiation, then high-dose radiation to eradicate his tumor. By the winter of 2002, he underwent a stem cell transplant because his bones had thinned to the point where a cough or sneeze would break ribs.

Each procedure hurt, but nothing came close to a 2005 surgery meant to reinforce his cancer-damaged sacrum with bone cement. Like sauce in a strainer, the cement seeped through Tuohy’s porous bone and to his sciatic nerve, inflaming it. Never had he felt such excruciating, enduring agony. It incapacitated him. He had to relearn how to walk. And while low-dose opioids previously eased his pain, after that surgery, he could only function by taking much larger amounts daily. He stuck to that regimen for about 12 years, at which point he started thinking, “I'm still alive, maybe I shouldn't be on this much?”

Tuohy beat the odds of his cancer, and has become an advocate alongside his wife, Robin, who serves as vice president of patient support at the International Myeloma Foundation. He maintains that, even compared to those brutal procedures, the first year he went off opioids completely was one of the worst of his life. He’ll still take small doses on occasion, during notably nasty pain flares, but he refuses to on back-to-back days.

“I'll never go through that again,” Tuohy said. “You're almost like a prisoner to it.”

Many cancer patients can relate. They worry long-term opioid use will lead to dependence, or impair hormone function, fertility, arousal and bone strength. Sage, for one, says she’s been on a mission the past several years to further winnow down her daily amount of oxycodone — a “nightmarish” process hallmarked by flu-like withdrawal symptoms including dizziness, nausea and diarrhea.

Paradoxically, prolonged exposure to opioids can also cause hyperalgesia, or an overly sensitive response to pain.

Prescription opioids, then, serve as the ultimate double-edged sword in cancer pain management. They’re maligned, having hooked millions of people in spirals of over-medication. In 2023, close to 8.6 million Americans aged 12 and older reported misusing prescription opioids sometime in the past year.

Yet, compared to other available drugs, they tend to offer the clearest path to relief. “In cancer, there's something driving ongoing injury and really remodeling the nervous system,” said Strand, of Mayo Clinic. “That's why opiates remain the cornerstone, because we see a continual injury and a continual ratcheting up of pain.”

Doctors argue that, under the watchful eye of seasoned oncologists and healthcare practitioners, opioids can be safely prescribed and the risks well mitigated. Data appear to support this. Two years ago, the U.S. recorded nearly 80,000 overdose deaths involving an opioid. In contrast to the early days of the opioid epidemic, illicit fentanyl, not prescription drugs, was a main driver of those cases.

While the addictive potential of opioids must be taken seriously, cancer doctors say they’re more concerned about the dramatically rising number of patients who need these drugs but cannot get them, either quickly or at all.

Supply constraints are one culprit. The government tightly caps the production of commonly prescribed opioids. Manufacturing facilities themselves are also aging and vulnerable to disruptions. Morphine and hydromorphone, sold as the brand Dilaudid, are just a couple of the opioids in short supply right now. Since most of the opioids used for cancer pain are lower-cost generics, companies have fewer economic incentives to rapidly patch up holes in the supply chain.

Even when a drug is in stock, insurance providers may not clear its use. Prior authorization, or the process by which insurers insist on approving a therapy before it’s prescribed, has become “the bane of our existence in cancer pain management,” said Strand, whose clinic sees north of 150 outpatient visits every week.

In his experience, Strand found it near impossible to get insurers to approve harder-to-abuse opioids like Xtampza or buprenorphine. And if they do, it’s not unheard of that out-of-pocket costs total hundreds of dollars a month — a financial barrier many patients can’t overcome.

Perla Macip-Rodriguez, a senior physician in Dana Farber’s palliative care division, ran into similar walls getting her patients certain longer-acting opioids. “The cost is something not possible for our patients,” she said. “So we never see it. We never prescribe it.”

Insurers are having both a “massive” and unpredictable impact on opioid prescribing, according to Dermot Fitzgibbon, a physician at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center and a professor of pain medicine at the University of Washington.

“The impression I have is that it comes down to cost, what is [deemed] cost effective, and what arrangements insurance companies have with opioid manufacturers,” he said. “The choices for opioid prescribing are largely taken out of the hands of doctors.”

The prescribing challenges don’t stop there.

4. The doctor

Judith Paice, in her more than 30 years as a pain doctor, has never seen so much attention paid to this one drug.

Cyclobenzaprine is an old medication used to relax muscles. Whether it’s valuable for anything else remains up for debate. Yet Paice, currently the director of Northwestern Medicine’s Cancer Pain Program, has noticed an “enormous” increase in cyclobenzaprine prescriptions, an uptick she attributes to a shift in treatment culture.

Scarred by the overdose epidemic, medical programs started steering trainees toward non-opioid painkillers. Veterans in the field now fear this messaging went overboard. They say their greener colleagues are so uncomfortable or unfamiliar with opioid prescribing that they won’t use these drugs even when the alternatives aren’t as beneficial, and that’s leaving patients suffering unnecessarily.

It’s not unusual, according to Paice, to see three to four less effective medications added to a patient's treatment plan.

“In the last 10, 15 years, opioid pandemic issues have really scared everybody — the public, the primary care doctors, the oncologists, even the pain doctors,” said Shengping Zou, an anesthesiologist at NYU Langone’s Center for the Study and Treatment of Pain.

Prescribing data reflect this anxiety. One study, published this March, examined 375 cancer patients referred to outpatient palliative care, and found opioid prescriptions for them dropped 80% from 2016 to 2021. The study authors wrote that such a decline raises concerns about the undertreatment of cancer pain, and indicates “educational initiatives are needed for physicians and patients to promote appropriate and safe use of opioids and remove associated misconceptions.”

The schooling dilemma goes beyond opioids, however. Pain programs across the board aren’t producing near enough experts to handle the growing number of patients living with cancer for years and years.

Many graduates “do not have adequate exposure to the complexities of cancer pain,” according to Fitzgibbon, and therefore struggle with the “single most important” part of treatment, which is accurately diagnosing the root cause of their patients’ discomfort.

With so few specialists, cancer doctors often take up the mantle. Yet they, too, lack some of the necessary expertise. Oncologists are also increasingly burnt out and don’t always have the extra time to respond to the vagaries of pain, which can wax and wane between a patient’s scans or appointments.

“Cancer pain is so unpredictable, and the treatments can produce a lot of problems,” Fitzgibbon said. “If you're going to manage it, you have to have a system that can respond to changing needs. It’s not good enough to see a patient in a month, in two months, in a year, because things change all the time.”

Sage insists the best choice made during her treatment journey was being assigned to a pain team — a luxury at some centers.

Oncologists “want you to be quiet, and I'm not saying that in a bad way. They just want you to be calm. They want you to be solved,” she said. “And the answer is: give them more pain meds. That's how I got up to six opioids in a day. They kept upping it because the answer just wasn’t there.”

In the view of MD Anderson’s Huh, the best way to improve cancer pain management would be to better educate oncologists and increase communication between them and the pain specialists. That would require less siloing of treatment center departments.

One workaround oncologists have turned to is referring to palliative care, which can have more in-depth discussions with patients and their families about pain treatment goals.

But if palliative care teams are expected to follow these patients over longer spans of time, they’ll need huge injections of resources. Healthcare authorities have, for more than a decade, sounded alarms that the U.S. needs thousands more palliative care physicians to meet the skyrocketing demand. That’s in addition to nurses, chaplains, psychologists and the support staff who contend with insurers and pharmacies.

Such a push would almost certainly have to come from the larger, wealthier academic centers.

“All of this trickles down to patients,” said Paice. “They hear the nuances of the opioid epidemic. They face obstacles when they go to the pharmacy. They feel judged and stigmatized and grow concerned about access, so they start to ration their medicines.”

“It's really an unfortunate perfect storm of inadequate pain control.”

5. The pain

Pain, especially the kind caused by cancer, has proven a formidable opponent. It stumps scientists, tricks doctors and haunts patients. Perhaps more than anything else, pain feels like it’s always two steps ahead.

There’s an eagerness to settle the score. At cancer centers, doctors are experimenting with layered treatment approaches, combining pain pumps, nerve blocks, opioid and non-opioid medicines, and even formerly controversial, now more accepted interventions like ketamine and marijuana.

“Right now, of the known mechanisms, we aren't necessarily missing great medications,” Beechy said. “I feel like we almost need a whole new category. But I have no idea how anyone would find that.”

There, researchers are making some headway. The National Institutes of Health in May reported that, in an early trial, a new therapy derived from a cactus-like plant appears safe and effective at controlling intractable cancer pain.

Top officials in the NIH’s department of perioperative medicine lauded how the therapy is easy to personalize and could “return some normality” to the lives of people with severe cancer pain.

Elsewhere, scientists at Harvard University and at Virginia Commonwealth University recently shed new light on the genetics behind nerve-infiltrating tumors as well as the inflammation responsible for causing chemotherapy-induced neuropathy.

Smaller biotechs also continue to take swipes at pain more broadly. Tris Pharma, a New Jersey-based developer, plans to seek approval for a dual-acting medication meant to emulate opioids but without the euphoria that makes them so addictive. Tris’ founder and CEO has said the fundamental goal of his company is to replace the opioid.

One of Paul’s startups, Rapport Therapeutics, is working on at least two experimental drugs for pain. The less advanced of them targets a nicotine-activated ion channel, and is being evaluated as a potential treatment in the chronic setting.

It’s unclear, maybe even unlikely, whether any of the medicines in development will end up useful for cancer pain, so patients are making due in the meantime.

Tuohy learned over many years how not to let pain run his life. He still has aches, along with neuropathy in both feet. “But I'm here,” he said. “That's more important, me being here with my family, than having to deal with pain.”

Sage has neuropathy as well. At night, the tingling gets so pronounced she feels like spiders are crawling on her legs. She refuses to try a new medication, though. There’s no room on her nightstand for another pill container.

She says she’s at peace knowing her pain level won’t ever be zero. She doesn’t need it to be. She wants to be cognizant, aware, and the pain tells her what’s lurking inside and how to respond.

Most days, that means Sage lives at what she calls a “5.”

“It's a pain that is non-releasing, a heaviness that weighs you down when you walk, a pressure on your hips so that you can't bend over,” she said.

“It takes your breath away.”

Visuals Editor Shaun Lucas and News Graphics Developer Julia Himmel also contributed to this story.