A key vaccine panel on Friday weakened recommendations that newborn infants immediately receive a hepatitis B shot, shifting a decades-old standard that’s helped protect children from the potentially deadly complications that can arise from a common viral infection.

The influential committee, known as the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices or ACIP, voted 8 to 3 to recommend what’s known as shared decision making when an expectant mother tests negative for the hepatitis B virus. Shared decision-making is a softer recommendation than a universal endorsement. For those who don’t receive the initial dose at birth, the panelists are advising a first shot no earlier than two months afterwards.

A second vote advised parents to consult with health care providers to determine whether testing should be offered before a child receives a subsequent vaccine dose. This decision breaks with established science and also weakens the current guidelines universally supporting a three-shot regimen, which is believed to be critical in ensuring long-lasting protection from hepatitis B. It’s unclear how effective only one or two shots are.

The panel initially delayed a decision on Thursday so panelists could further review the language underlying each voting question.

“The hepatitis B vaccine program is one of the world’s greatest achievements in medical health in the protection of children,” said Joseph Hibbeln, a psychiatrist and neuroscientist and one of the dissenting panelists. “This has a great potential to cause harm, and I simply hope that the committee will accept its responsibility when the harm is caused,”

“We are going to experience increased rates of hepatitis B, and it is not the right thing for us to do,” added Cody Meissner, an expert in pediatric infectious disease epidemiology, vaccine development, and immunization safety. Meissner also voted against the new recommendations.

The hepatitis B virus can be transmitted from mother to newborn during birth, as well as through infected body fluids. Newborns are much more likely than those over the age of 5 to contract chronic infections, which can lead to progressive liver disease, cirrhosis or liver cancer later in life.

Women can be infected without realizing it and, while testing can be done during a prenatal visit, lack of access to healthcare facilities or errors during and after testing can prevent mothers from knowing their status. The Vaccine Integrity Project, an initiative started by a group at the University of Minnesota, found in a recent report that anywhere from 12% to 18% of women aren’t tested during pregnancy, and only 42% of pregnancies with a positive diagnosis received the recommended care.

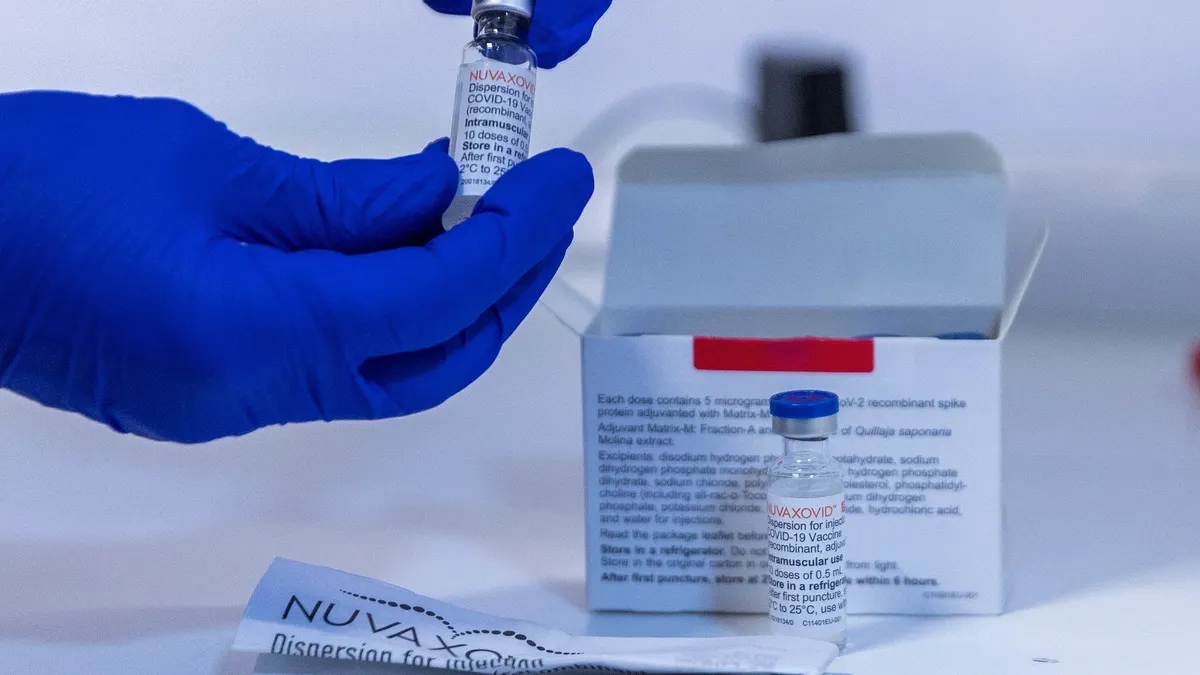

Vaccines for hepatitis B were first introduced in the 1980s, and ACIP in 1991 began recommending that all infants get the first of a three-shot regimen within 24 hours of birth. Since then, vaccination has proven to be more than 90% effective at inducing immunity, with protection lasting decades and possibly for life.

One study published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2023 credited vaccines with spurring a 99% drop in infections among U.S. infants, children and young adults between 1990 and 2019. And a recent pre-print study from several U.S. institutions projected that delaying vaccinations by even two months after birth would lead to over 1,400 preventable infections, 304 cases of liver cancer and 482 related deaths.

“The hepatitis B vaccine is the most effective way we have to prevent the infection in babies and prevent the subsequent liver failure and liver cancer later on in life,” said Kawsar Talaat, an infectious disease physician and associate professor in the Department of International Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, in an interview with BioPharma Dive.

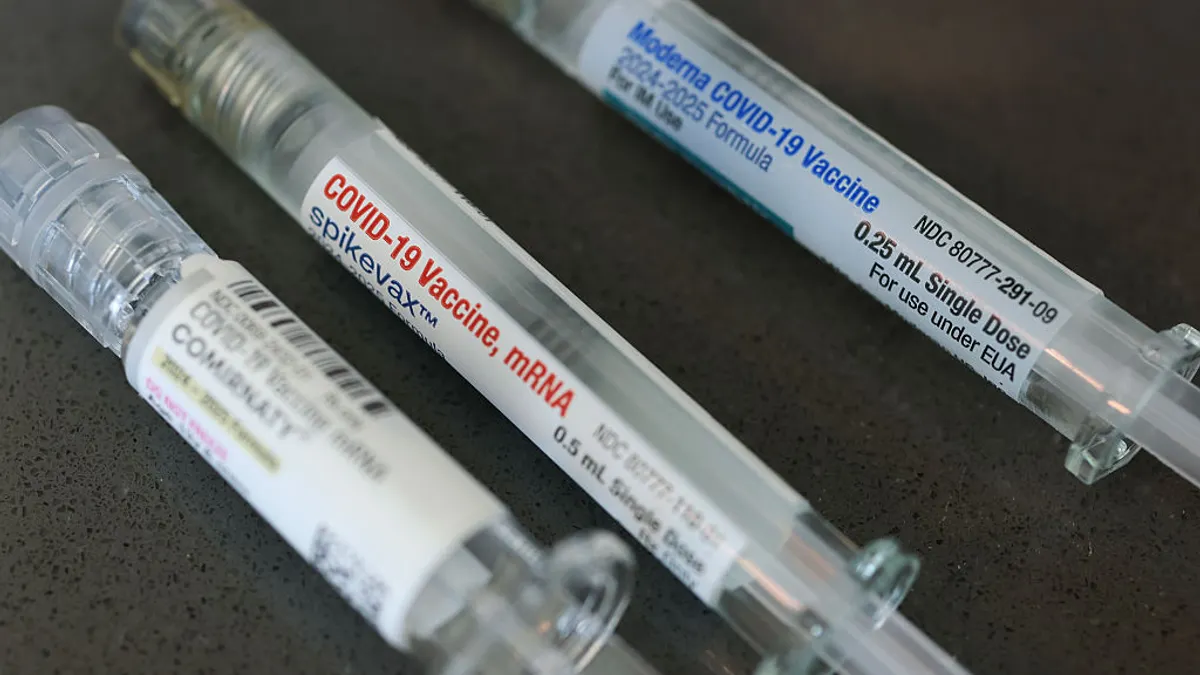

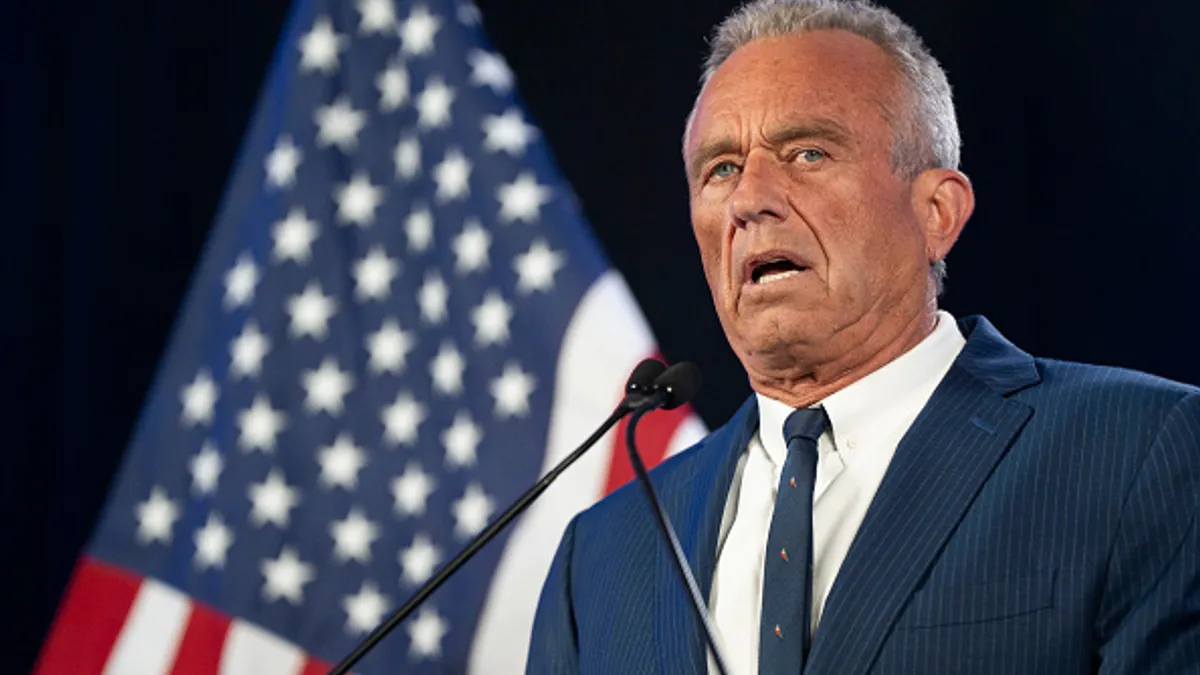

Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. remade the committee in June, abruptly ousting all of its previous members and replacing them with panelists more aligned with his skeptical views of vaccines. The reformed panel has since made small inroads towards limiting vaccine access. After initially questioning the safety and impact of COVID vaccines, ACIP softened recommendations supporting use of the shots. It also voted to split MMR and varicella shots and recommended that a particular preservative be taken out of flu vaccines.

Several medical groups have spoken out against the reformed ACIP, with some organizations promoting their own vaccine recommendations. Previously ousted members of the group also called for the creation of a new alternative, citing its “inexperienced and biased” members.

In the past, CDC work groups would meet ahead of an ACIP meeting to prepare data briefings. However, working group members, as well as Debra Houry, the CDC’s former chief medical officer, have said these groups haven’t regularly convened, and experts on vaccine safety and development told Stat News they were not consulted ahead of the meeting. Presenters included a lawyer, Aaron Siri, who’s sued vaccine manufacturers, and Cynthia Nevison, a climate researcher with ties to anti-vaccine groups.

“The ACIP is totally discredited. They are not protecting children,” Bill Cassidy, a Republican senator who helped confirm Kennedy as HHS Secretary, posted on the social media platform X.

The group met in September to discuss delaying newborns’ hepatitis B shot, with some citing potential safety risks and others expressing confusion as to why a change was being considered. They tabled a vote on the issue, leading to a new gathering months later.

At the meeting’s start, Robert Malone, who served as committee chair on Thursday, said the vote was delayed so more data could be gathered to guide the panel. “When gaps in the evidence emerge, the responsible action is not to push forward,” he said.

Yet the committee struggled to move forward after hearing that evidence.

In one presentation, Nevison argued that other, “targeted” measures had a greater impact on plummeting hepatitis B infection rates than a birth dose, and downplayed the regimen’s effectiveness at preventing disease long-term. Mark Blaxill, an anti-vaccine activist, contended that more safety data should be generated via new placebo-controlled clinical trials, echoing talking points from Kennedy. (Scientists have noted how testing a vaccine against a placebo, when an effective shot currently exists, could be considered unethical.)

Meissner was skeptical of both presentations, pointing to a lack of evidence that hepatitis B vaccines cause any meaningful harm, and noting how the disease has “gone down” in the U.S. because of the current immunization program.

“In your opinion,” Malone responded, prompting Meissner to quickly counter “those are facts.”

Meissner was joined by a liaison to the American College of Physicians and representatives from hepatitis B vaccine manufacturers, GSK, Sanofi and Merck & Co. in defending the shots’ merits. The liaison, Jason Goldman, pleaded with the panel to “look at all evidence and data and not cherry-pick,” and company representatives argued that there’s no credible data pointing to safety risks.

“Please have respect for the American public and the science and do what is right by making sure you use a process that we can depend on,” Goldman said.

The committee had originally been scheduled to vote on three questions on Thursday, among them whether to endorse shared decision making for an expectant mother who tests negative for the virus. However, multiple members claimed they weren’t fully aware of the exact recommendations they’d be voting on ahead of the meeting, and requested more time to iron them out.

Recommendations from the meeting go to the head of CDC, whose acting director is Kennedy’s deputy Jim O'Neill. New guidelines affect insurer coverage for immunizations.

The panel is set to discuss the broader childhood immunization schedule on Friday, though it won’t vote to make any specific changes.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated with the outcome of ACIP’s votes.