A biotechnology firm hatched by two prominent researchers publicly debuted on Friday, aiming to use a new regulatory framework to quickly develop many gene editing treatments for rare diseases.

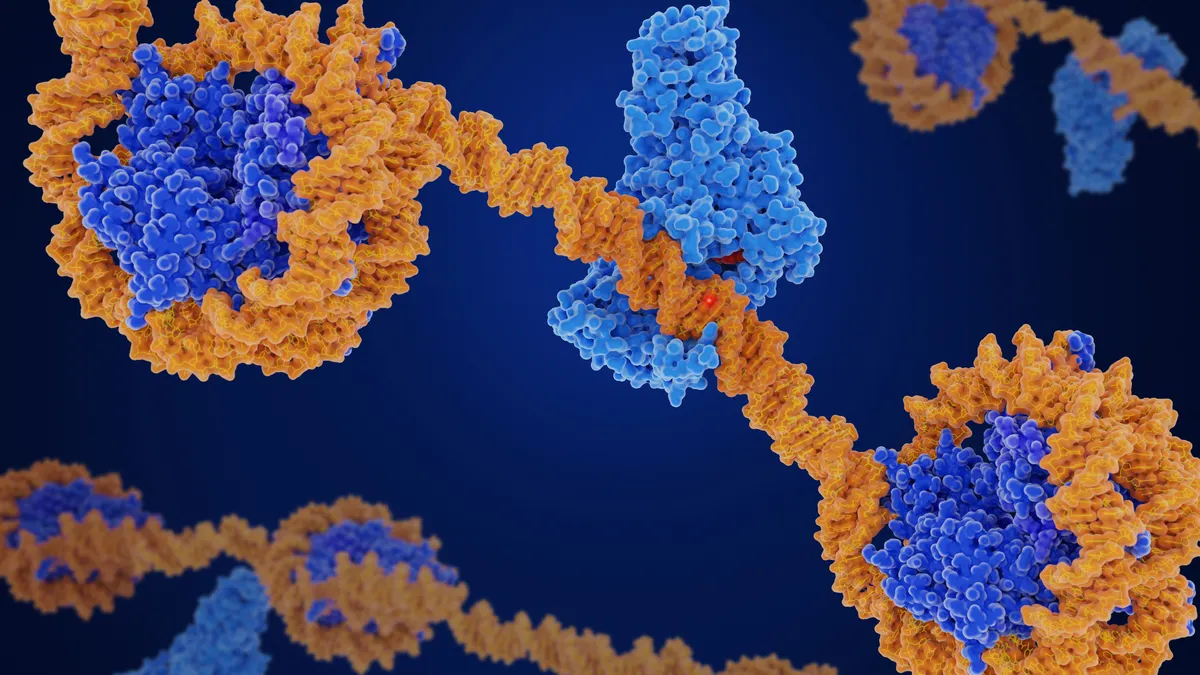

Called Aurora Therapeutics, the startup was co-founded by Nobel laureate Jennifer Doudna and genetic medicine expert Fyodor Urnov and seeded by Menlo Ventures. It intends to simultaneously work on multiple therapies for the same condition, each of which target different genetic mutations, and quickly advance them with the help of the Food and Drug Administration’s recently unveiled “plausible mechanism” pathway.

Aurora is led by Ed Kaye, a veteran biotech executive and former leader of Sarepta Therapeutics and Stoke Therapeutics. Menlo provided $16 million in seed funding to the startup, which will first test its approach on phenylketonuria, a genetic disease that disrupts the body’s ability to metabolize an important amino acid.

Aurora’s emergence represents the latest attempt to solve a business problem that’s slowing the progress of genetic medicine.

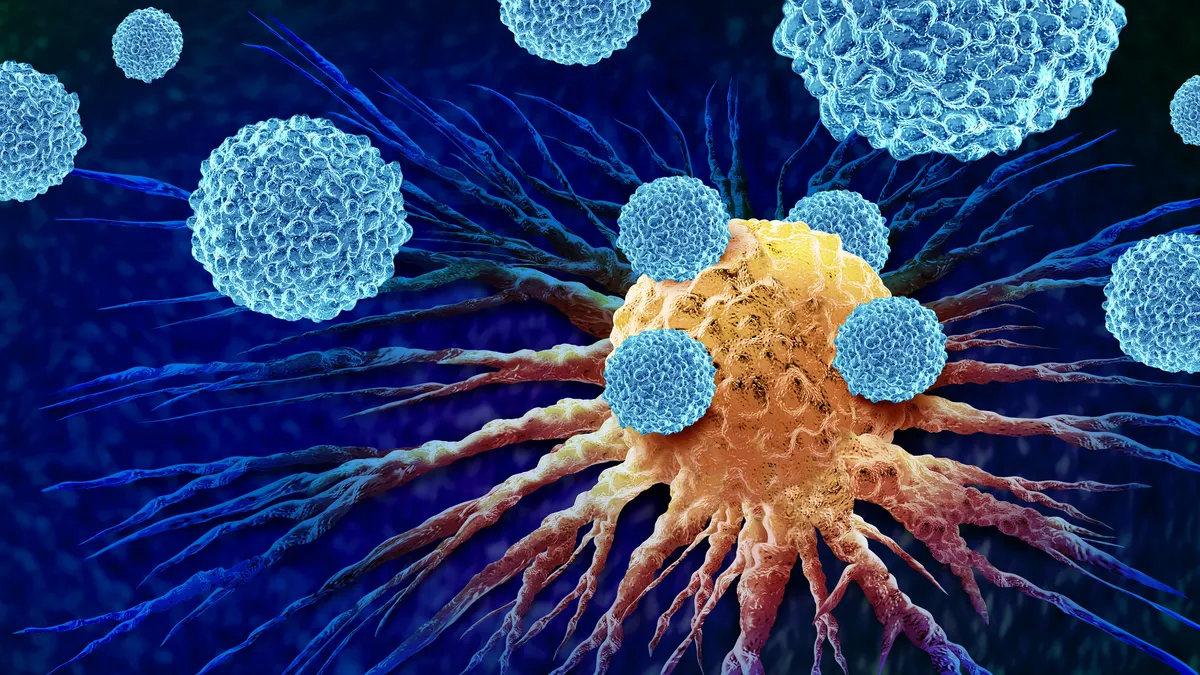

Advances in sequencing technologies and powerful tools like CRISPR have made it possible to rapidly pinpoint and correct genetic errors known to drive thousands of rare diseases. But the small number of patients with those conditions and the exorbitant costs of developing gene-based treatments for them make for a daunting investment proposition, leaving many would-be therapies out of reach.

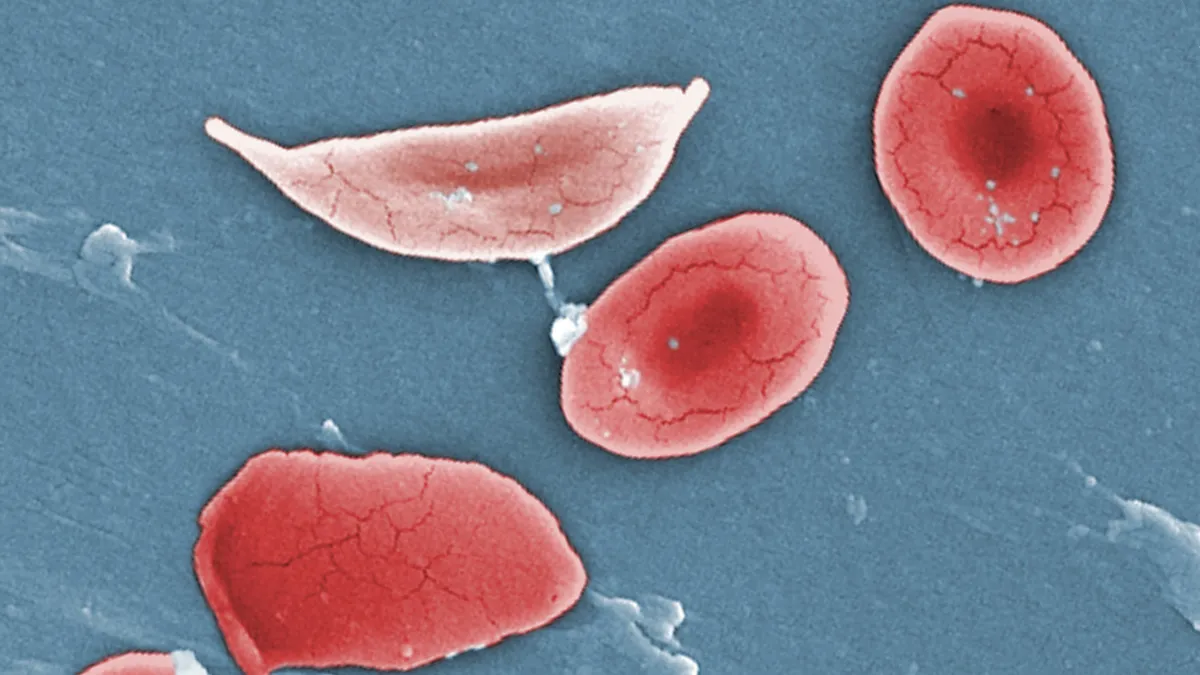

Notable headway has been made in recent years, though. Academic researchers have, in multiple cases, designed custom therapies for specific individuals. The most prominent example came last year, when researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and elsewhere designed and developed within months a CRISPR-based treatment for a critically ill baby named KJ Muldoon. That treatment has helped stabilize KJ’s condition.

KJ’s story caught the eye of Food and Drug Administration leaders. Last November, Commissioner Marty Makary and top deputy Vinay Prasad featured it while explaining the plausible mechanism pathway, a regulatory tool meant to speed along treatments for rare and serious conditions. Crucially for gene editing companies, they described how developers could use data from an initial approval — say, for a person whose disease is tied to a specific genetic mutation — to make minor modifications that could support additional clearances for people with other mutations.

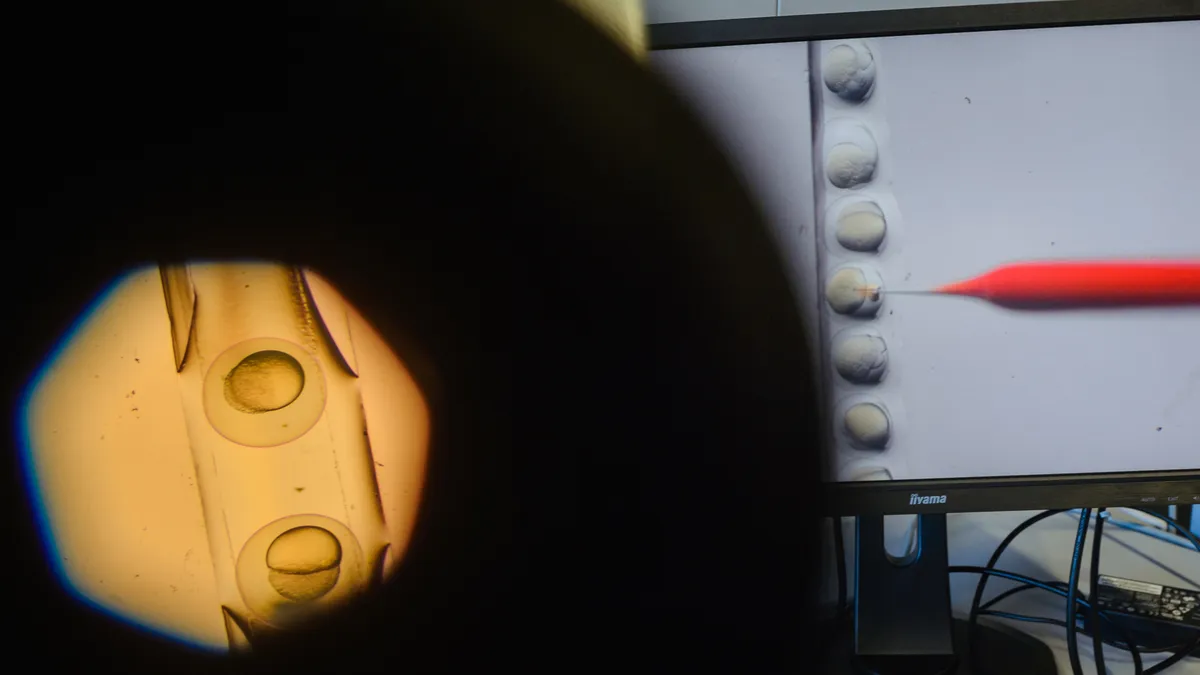

Aurora will test that blueprint. Leaning on technical advances enabling the faster design and production of gene editing components, the company is working on what it claimed in a statement would be the first platform to treat the types of mutations historically “impossible to address at scale.”

According to Kaye, Aurora will start out by focusing on a disease’s more frequent mutations. Doing so would enable it to get a “commercial foothold that generates revenue” while building a way to efficiently develop subsequent therapies for rarer mutations.

“Eventually, we could get to a point where we could very quickly respond to individual patient needs,” as was the case with baby KJ, Kaye said. “But we first really need to have a well-developed system that is sustainable before we go after very, very rare indications.”

Aurora believes it can build that system by starting with phenylketonuria, or PKU. The disease is caused by a wide range of mutations to a gene called PAH. While it’s currently managed with lifelong therapy, dietary restrictions and monitoring, those approaches aren’t curative and can still leave patients with cognitive deficiencies.

PKU is also well-understood biologically and, as a result, long been a target of genetic medicine. But unlike previous efforts, Aurora is designing multiple therapies. The first will simultaneously address the three most common PKU-causing mutations. Aurora will then broaden its approach and add more.

Kaye believes that, as a result, the disease “fits in the plausible mechanism pathway perfectly.”

“We understand the proximate cause of the disease, and we know how to address it,” he said.