Regulators in the U.S. and Europe recently determined that a popular group of drugs for weight loss and diabetes don't heighten the risk of suicide. New data published in the Journal of the American Medical Association on Tuesday appear to back up those assessments, though researchers cautioned that there’s still more work to be done.

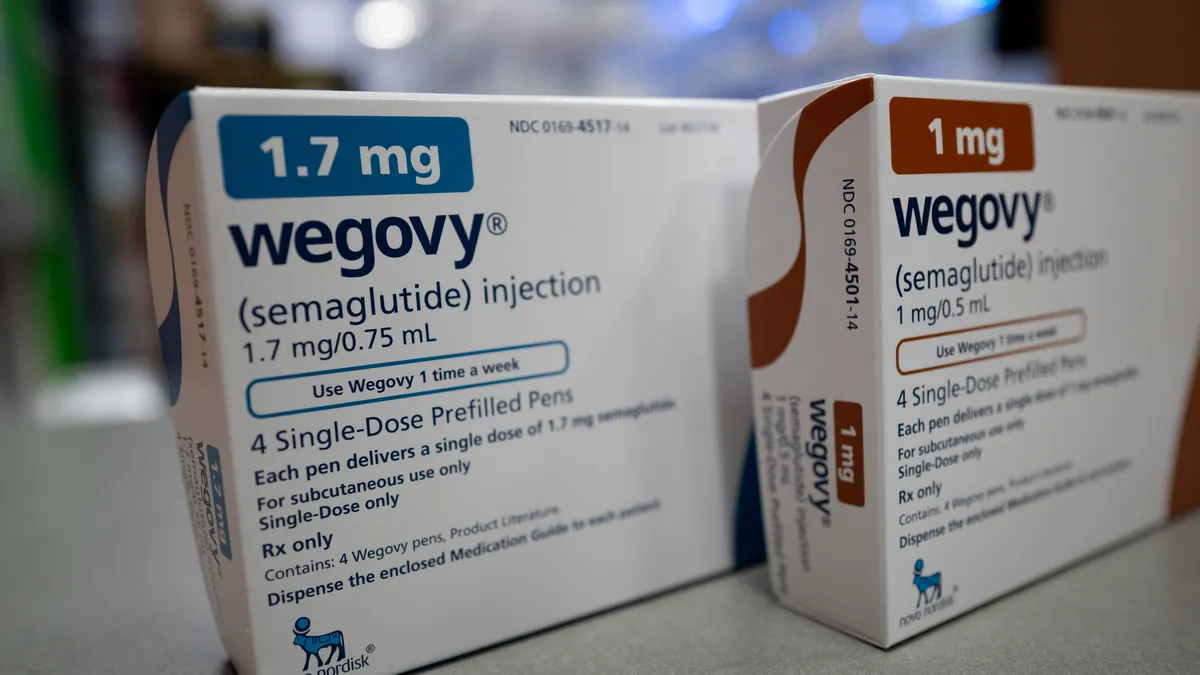

The findings come from a pair of large, retrospective evaluations. One reviewed the effects of a so-called GLP-1 drug or another diabetes medication on the risk of suicide or other mental health problems in nearly 300,000 people in Sweden and Denmark. The other looked at the incidence of suicidal thoughts or depression symptoms in 3,600 study volunteers who received the obesity drug Wegovy or a placebo in studies Novo Nordisk ran to secure regulatory approval.

Taken together, the two studies found there wasn’t a greater risk of suicide or poor mental health outcomes in people taking GLP-1s instead of a placebo or comparator drug. The results are notable, as millions of people already take these medicines to lower blood sugar and weight. Adoption is expected to climb in the years ahead as their use is broadened to include other conditions. But in an accompanying editorial, researchers warned that the findings are part of an “incomplete puzzle” that will require further study.

The study of patient registers in Sweden and Denmark found 77 people who took Novo’s GLP-1 drugs Ozempic or Victoza committed suicide between 2013 and 2021, compared to 71 who were treated with a different type of diabetes medicine. That difference wasn’t statistically significant, nor was the result of a separate analysis of people with a history of psychiatric illness.

People on GLP-1 drugs had a slightly lower risk of self-harm than the comparator group, and a similar risk of depression or anxiety-related disorders, the researchers found.

The second analysis examined patient surveys evaluating depressive symptoms as well as suicidal thoughts or behavior in people who received Wegovy in four different clinical trials called STEP 1, 2, 3 and 5. Pooled results from the first three trials showed people on Wegovy had a slightly better score than placebo recipients on depression symptoms, while in the fourth study there was no difference. Overall, the average scores of trial volunteers “remained in the range of no/minimal symptoms of depression” regardless of which study group they were in, the researchers wrote.

In STEP 1, 2 and 3, eight volunteers who took Wegovy and seven who received a placebo reported experiencing suicidal thoughts. In STEP 5 one drug recipient and two in the placebo group reported the same.

Still, the findings were limited, wrote Timothy Anderson, an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh and Deborah Grady, a professor emeritus at the University of California, San Francisco, in the editorial. Results from the Sweden and Denmark analyses could be confounded by “unmeasured differences” between the study groups, Anderson and Grady noted.

Novo’s trials excluded people who’d reported severe depression symptoms or had a history of major depression, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder within two years of enrollment. The evaluations also didn’t assess whether drugs that affect another gut hormone called GIP — a target of Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro and Zepbound — could have an effect on mental health symptoms, they wrote.

“While both studies are reassuring, neither fully answers the question of whether these drugs are safe in those with preexisting mental health problems,” Anderson and Grady wrote. They cautioned that “continued vigilance in monitoring mental health symptoms is essential.”