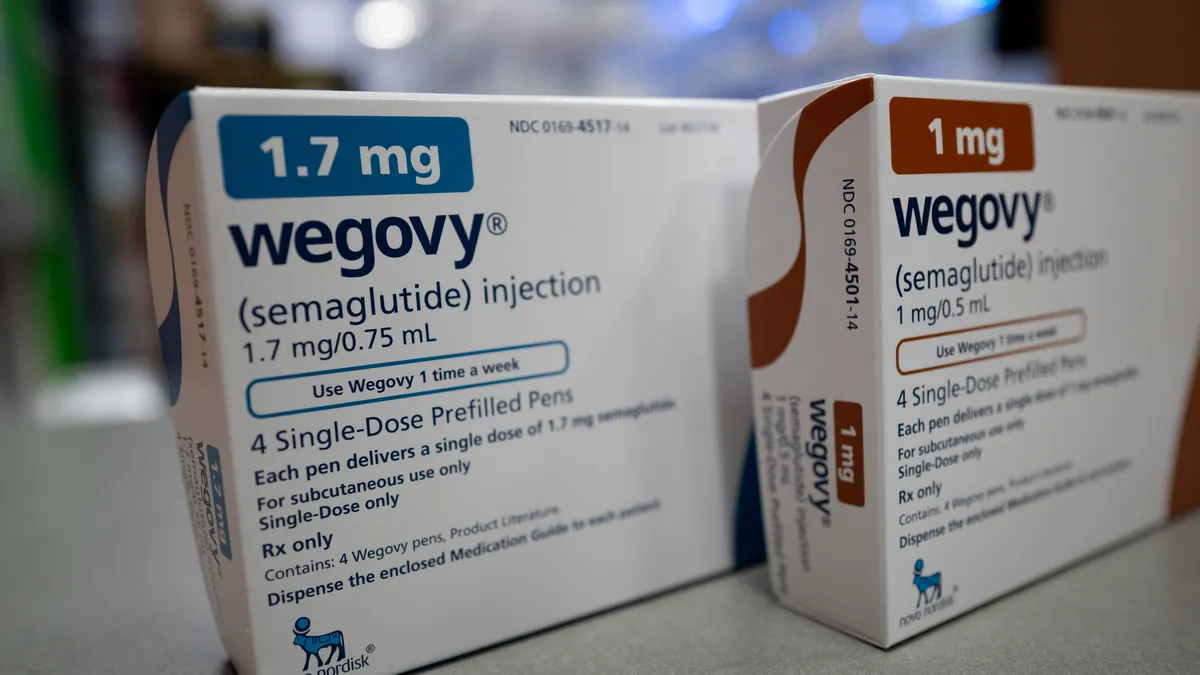

Zepbound, an in-demand weight loss drug from Eli Lilly, helped people in a large clinical trial lose significantly more weight over 18 months than Novo Nordisk’s rival treatment Wegovy, results released by Lilly Wednesday show.

The head-to-head results are a key finding that may help Lilly wrest greater share of a pharmaceutical drug market that’s forecast to eventually exceed $100 billion in annual sales. For that reason, Lilly’s study, called SURMOUNT-5, has long been circled by investors and analysts on Wall Street as one of the year’s most important drug studies.

Lilly only disclosed summary data in its Wednesday statement, indicating it will share fuller findings at a medical meeting next year. According to the results Lilly made available, trial volunteers with obesity or who were overweight with related health problems lost an average of 20.2% of their bodyweight from taking Zepbound, significantly more than those who received Wegovy, who lost 13.7% on average. That translated to an average of 50 pounds lost among Zepbound-treated participants, versus 33 pounds for those on Wegovy.

Nearly one-third of people given Zepbound experienced weight loss of 25% or more, compared to 16% in the Wegovy group, Lilly said.

For both drugs, the most common side effects were gastrointestinal and, according to Lilly, generally mild to moderate in severity. Side effects are being closely watched, as commercial use of Zepbound and Wegovy has shown many people taking them later discontinue treatment.

Investors and analysts had, to varying degrees, expected Zepbound to prove superior to Wegovy, based on studies that suggested Lilly’s drug spurred more weight loss as well as analyses of patient records that hinted the same. Still, the data pushed Lilly shares higher by nearly 3% Wednesday morning.

While it will be months before Lilly can begin marketing Zepbound’s weight loss advantage over Wegovy, the trial’s findings could prompt doctors to favor the weekly shot, which acts on two different gut hormones to help regulate appetite and blood sugar levels. (Wegovy, by comparison, acts on a single hormone.)

However, market competition between the two drugs will be moderated by unsteady supply of the two drugs, which Lilly and Novo have struggled to make in sufficient quantities as demand has grown.

“Zepbound is in a class of its own as the only FDA-approved dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist obesity medication, and it's changing how millions of people manage this chronic disease,” said Leonard Glass, head of global medical affairs at Lilly’s cardiometabolic division, in the company’s statement.

Called SURMOUNT-5, Lilly’s study enrolled around 700 people who were identified as having obesity based on their body mass index, or who were overweight and also had a weight-related complication like heart disease. To enroll, participants also needed to have tried at least one attempt at weight loss.

Volunteers were randomly assigned to weekly shots of either Zepbound or Wegovy and followed for 72 weeks. Investigators assessed percentage weight loss from the study’s baseline measurements as the main measure of efficacy. Secondary endpoints included the share of people in each group that achieved specific thresholds like 10% or 20% weight loss.

In addition to meeting the study’s primary goal, Zepbound outperformed Wegovy on the trial’s five key secondary endpoints, too.

Lilly’s results will likely shape the market for some time, as Zepbound and Wegovy are well established as the primary approved products.

Still, oral drugs acting on GLP-1, the hormone that both Zepbound and Wegovy target, as well as new treatments aimed at GLP-1 and other hormonal receptors are advancing through development.

One of those is an experimental Novo drug called CagriSema. A closely watched trial of CagriSema, which combines Wegovy’s active ingredient with a second compound, is due to read out results in the fourth quarter of 2024.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated with additional detail and mention of Lilly’s stock price change.