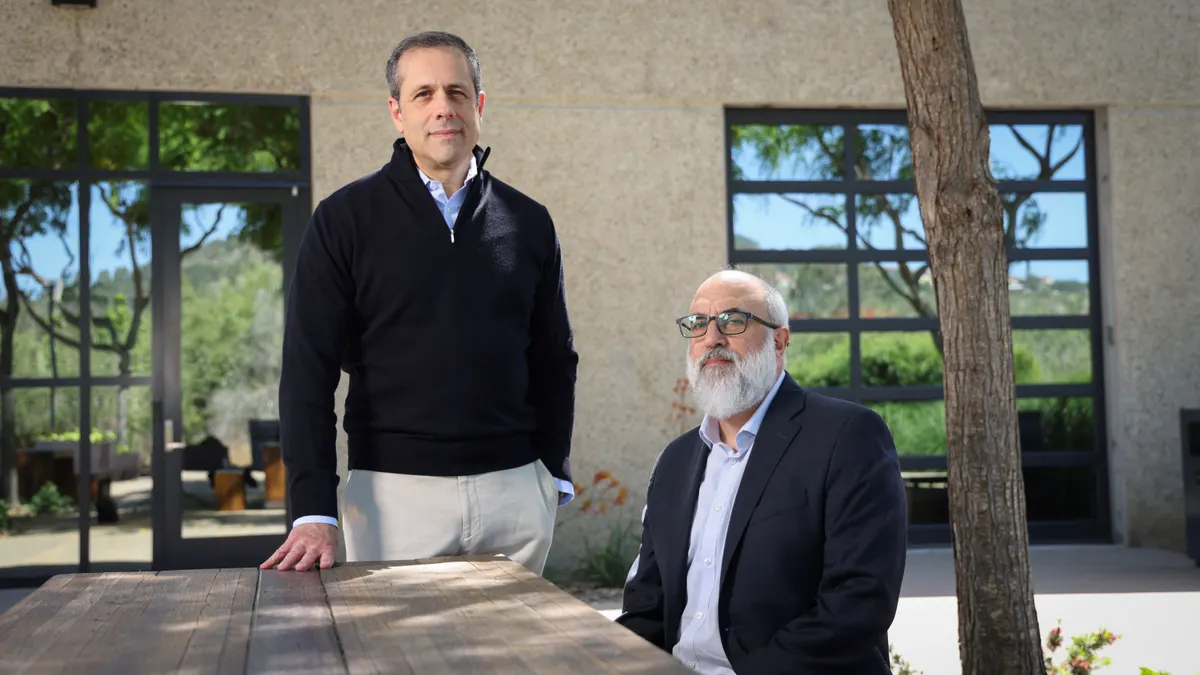

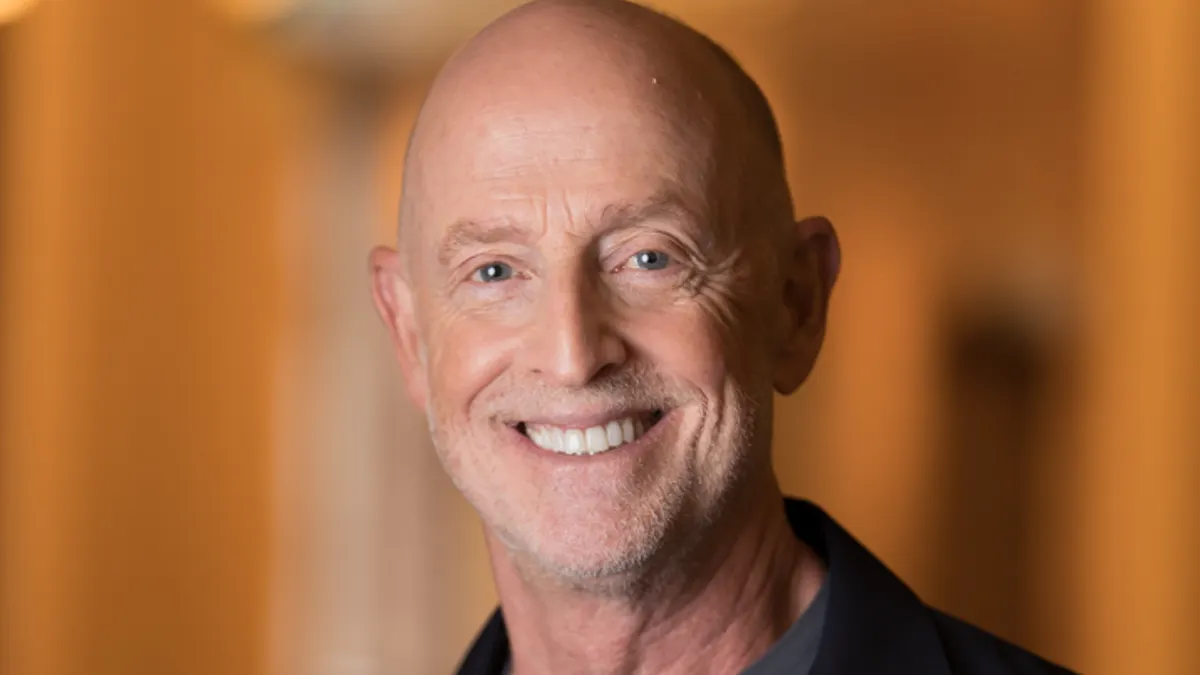

Otello Stampacchia has watched the biotechnology industry survive many dark days in the two decades he’s led one of its premier investment firms.

Stampacchia formed Omega Funds in 2004, just a few years before the Great Recession caused a lengthy pullback in biotech investment. An exuberant period, during which a record number of drug companies went public, followed, only to later give way to another downturn that again tested the fortitude of biotech investors.

Companies and their backers have a new set of challenges in 2025. Layoffs and leadership changes at public health agencies, competitive pressure from China and cuts to U.S. science funding have left biotech startups with a state of disquietude. Initial public offerings are harder than ever to price. Many public companies are worth less than their cash holdings, and face growing pressure from investors to shut down. And politics have seeped into science, eroding confidence in proven medical interventions like vaccines.

Still, Stampacchia, whose firm raised a $647 million fund in July, is optimistic that better days lie ahead for biotech. The industry needs a reset that will “lead to the greater good,” he told BioPharma Dive.

“This is medicine, and medicine sometimes tastes bitter,” Stampacchia said.

BioPharma Dive spoke with Stampacchia about biotech investing. The following conversation has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

BIOPHARMA DIVE: How has the slowdown in biotech IPOs affected your decision-making as an investor?

OTELLO STAMPACCHIA: We like to tell our companies to stay private for longer, if possible. It's been more than five years now that we've been operating under the assumption that the IPO market should not be our road to a potential exit, which is usually via some acquisition.

With M&A, you’re selling to sophisticated buyers who know what they want. In the IPO market in our space, you're selling to relatively sophisticated public investors. But there's a lot of other variables that come into play — interest rates, the environment and so on. Generalists have basically deserted the space for quite a bit now, because there's a more attractive, in their opinion, risk-reward profile somewhere else.

Has anything changed this year, when IPO activity appears especially slow?

STAMPACCHIA: What we are seeing — and this could lead to some changes, actually — is the repercussions of some of these public investors being somewhat distressed. These were investors people traditionally used to go to syndicate the later-stage rounds. That's going to become a lot harder, which is going to make valuations more attractive for those later-stage rounds. So we are doing a bit of a tactical reallocation toward that later-stage opportunity set, because it's quite an interesting sweet spot.

What do you make of investors pressuring struggling, publicly traded biotechs to close and return cash to shareholders?

STAMPACCHIA: Necessity is the mother of all invention, as they say. There is a trend about not willing to give management the benefit of the doubt anymore. What you are seeing is a return to discipline, which has been quite a bit loose in the years where everybody could go public. Capital was abundant, interest rates were lower, all that.

It all stems from the fact these public investors are suffering themselves. As a result, they need more liquidity, and some of these stocks are illiquid. It's more efficient to return that cash to shareholders. Each situation is a little bit different, but the reality is these companies all burn cash. If the cash is not going towards clinical programs that could potentially deliver either stock price appreciation or, even better, an M&A exit, it's a logical and rational decision to try to get some of the cash back.

Overall, the market is trying to be more rational than it has been in the past. In the long term, it's not pretty when you're the employee of a company that is having to wind down. But on the macro level, it’s kind of healthy.

What can be done earlier to make sure fewer companies end up in this spot?

STAMPACCHIA: The issue is the step where the company goes from a stricter governance model, which is what we try to implement as venture investors. A stricter governance model implies a very close collaboration between those investors, the board members and management. And that collaboration should — not always, but should — result in a tighter screw on what programs get funded and go forward, and the bar for those programs to move forward.

When that collaboration and governance starts to become looser, some of these problems emerge. Companies spend money on unproductive projects, raise more money than they should, or don't raise enough. If I were to think, what should we do differently, it would be to ensure that control, governance and collaboration between those two important constituencies — the providers and users of capital — remains very tight for longer.

A dirty little secret in the industry is that the reason companies love to go public are twofold: One is to get access to other sources of capital, because there's only so much money on the private side. The other, in my opinion, is that they can eventually get rid of their venture investors on the board. We have certain practices, which are not always correct, but they're usually fairly accurate, as they've been repeated hundreds of times across thousands of companies. Access to different sources of capital is great, but then you start losing some of the discipline, collaboration and governance.

Does the politicization of mRNA vaccines and pullback in federal funding make you more hesitant to invest in vaccines?

STAMPACCHIA: To be fully transparent, it's not like we have backed hundreds of vaccine companies. But the short answer is yes.

The public health implications are more profound — obviously, measles and all that. The issue is vaccine hesitancy, which is potentially quite dangerous to society and public health. But from the very narrow investor mindset, it makes investing in that whole field much trickier. Across the spectrum in the community, there will be more hesitancy to invest in these companies. And that's not great.

How have leadership changes at the FDA affected the sector, from your vantage point?

STAMPACCHIA: We probably need a bit more distance and time to figure out how impactful these changes are. It is fair to say that there's a perception of instability, and perhaps even more importantly, a lack of consistency from the agency.

All the statistics that I can find, as well as interactions our companies have with the agency, [show] the reviewers are doing their job. The issue is how is this going to play out in not just the short term, but the medium term, and how it will affect this perception of instability. Because perception of instability is instability in its own way.

How has the inflow of biotech assets from China influenced your decision-making?

STAMPACCHIA: This is relatively new, at least in terms of the percentage of these assets that have been licensed or acquired over the last two or three years. So there's quite an impact. And there's not a lot of visibility on companies in the country, versus we have a lot of visibility on companies in Europe. We need to do our job of competitive landscaping and positioning better.

Fundamentally, and particularly for biologics, if there is a very validated target that could be improved by half-life or some heavy-duty iteration on the biological structure, and if it is a large enough market, somebody in China is probably doing it. And they have an advantage with the early stage trials.

I don't think U.S. or European regulators understand that this is a massive advantage in enrolling patients early. That advantage is perhaps even more important than the advantages they have on [manufacturing] and iterating on biologics. The real speed is in the clinic to prove stuff. That has profound political implications for countries that want to maintain a healthy pharma/biotech industry.