Dive Brief:

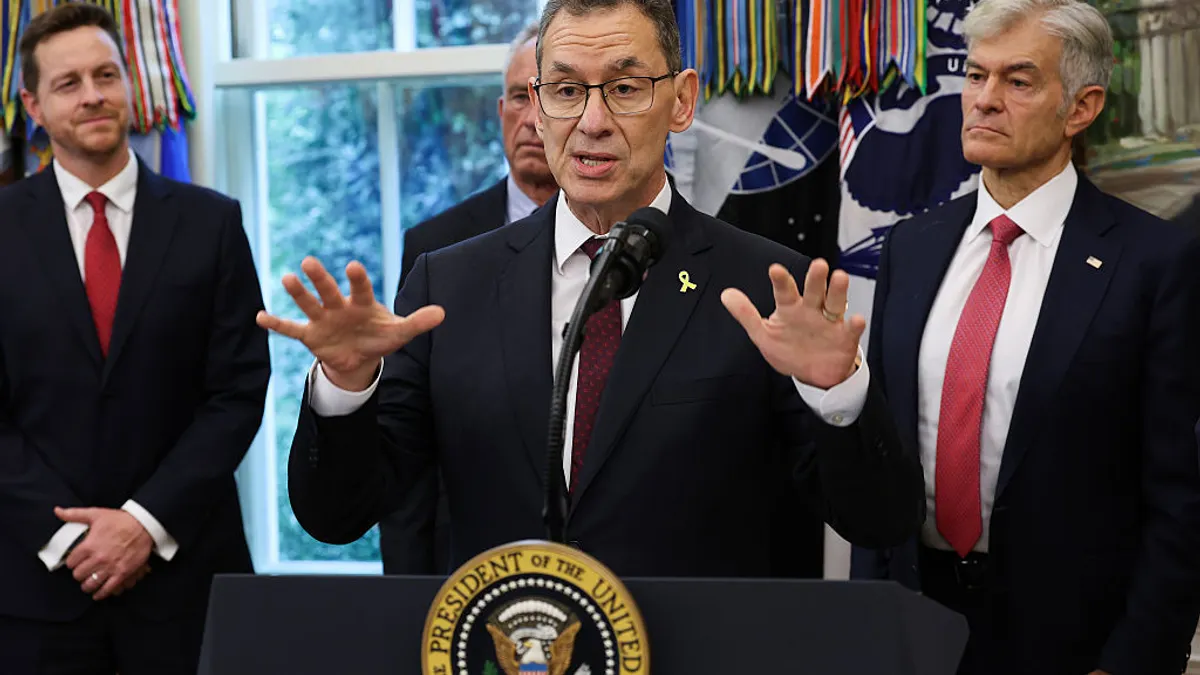

- Pfizer on Tuesday signed a deal with the Trump administration to offer “most favored nation” drug prices to every state Medicaid program and discounted prices directly to other consumers through a new website.

- The agreement also delays, by three years, any tariffs on Pfizer drugs that might arise from the ongoing “Section 232” probe into the effects of pharmaceutical imports on national security. Pfizer, which hadn’t yet joined its peers in making large U.S. production pledges, additionally vowed to spend $70 billion on “research, development and capital projects” in the next few years.

- Specific terms of the deal remain “confidential,” Pfizer said. But it was announced a day after a deadline expired for big drugmakers to respond to President Trump’s call to align U.S prices with those overseas. The deal also followed a flurry of recent moves by drugmakers, as well as the industry lobbying group PhRMA, to sell medicines at lower costs by bypassing insurers and pharmacy benefit managers.

Dive Insight:

The actual impact of Tuesday’s agreement on the prices paid by U.S. consumers may be limited. Since 1990, Medicaid, which provides coverage for millions of Americans, has gotten reduced prices through a mandatory drug rebate program that gives it a 23% discount off the average price paid by wholesalers and other large purchasers.

Additionally, most people in the U.S. access drugs through commercial or government-backed health plans. That could narrow the likely reach of these newer, direct-to-consumer programs to people without insurance or who are willing to pay out-of-pocket — such as in a situation where insurance co-pays are higher than a drug’s cash price.

Nonetheless, in part because of Trump administration pressure, multiple drugmakers have set up ways to sidestep insurers and sell discounted medications to consumers. Among them are Eli Lilly’s obesity shot Zepbound, which starts at $399 a month, and Bristol Myers Squibb and Pfizer’s blood-thinner Eliquis, which costs $346 per month.

Some of the drugs being offered through these programs won’t have market exclusivity for long, though, meaning cheaper, generic alternatives could soon be available. Eliquis loses patent protection in 2026, while Xeljanz, a rheumatoid arthritis drug the White House touted as part of the new Pfizer program, also goes off patent next year.

What’s more, cancer and rare disease drugs that can cost tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars per year haven’t been involved in direct-to-consumer channels as of yet. Those drugs are often prescribed by specialists, delievered through special pharmacies and administered in healthcare settings, complicating their potential inclusion.

Carter Gould, an analyst at the investment firm Cantor Fitzgerald, argues that the Pfizer deal "appears largely benign" and is "more optics than bite.”

"For all the hype and commentary around delivering a transformative win for lower drug prices, it’s worth noting that Pfizer’s PR didn’t change a single financial metric or piece of guidance," Gould wrote in a note to clients.

In its statement, the pharmaceutical giant said it has committed to a “balanced global pricing approach that continues to recognize the value of innovation while ensuring prices in the U.S. and other developed countries are both reasonable and sustainable,” but didn’t state how closely those prices would be aligned.

The White House said Pfizer has agreed to “repatriate” to the U.S. any increased revenue it sees from higher prices elsewhere.