John Kulman, then a senior research executive at CRISPR Therapeutics, was on vacation in Kennebunkport, Maine, three years ago when he snuck away to his laptop.

The “vacation from his vacation,” he said, was prompted by intriguing scientific research sent by Kulman’s former boss a few weeks earlier. The paper detailed ways in which the thymus, a small gland in the upper chest, had the ability to direct certain immune cells to stop the body from mistakenly attacking itself. It even included a “treasure trove” of drug targets to worth with.

Kulman was struck by its prospects. Engineering a therapy that could get to the thymus and coerce it to act, he thought, might hold the key to treating a wide range of autoimmune conditions. He finished reading the paper and, from his hammock, told his former boss, Jo Viney, and Polaris Partners partner Alan Crane to pursue it.

“They came back and said, ‘Well, why don't we do this?’” recalled Kulman. The project they pursued is now known as Zag Bio, which emerged from stealth on Tuesday with $80 million in funding from nearly 10 investment firms and plans to treat autoimmune conditions with drugs that target the thymus.

Jason Cole, Zag’s CEO, describes the concept as “analogous” to research on regulatory T cells, or Tregs, that recently won a Nobel prize. Treg cells are a specialized type of immune cell that guards the body from attacking itself and that have been the focus of a number of emerging cell therapy startup companies.

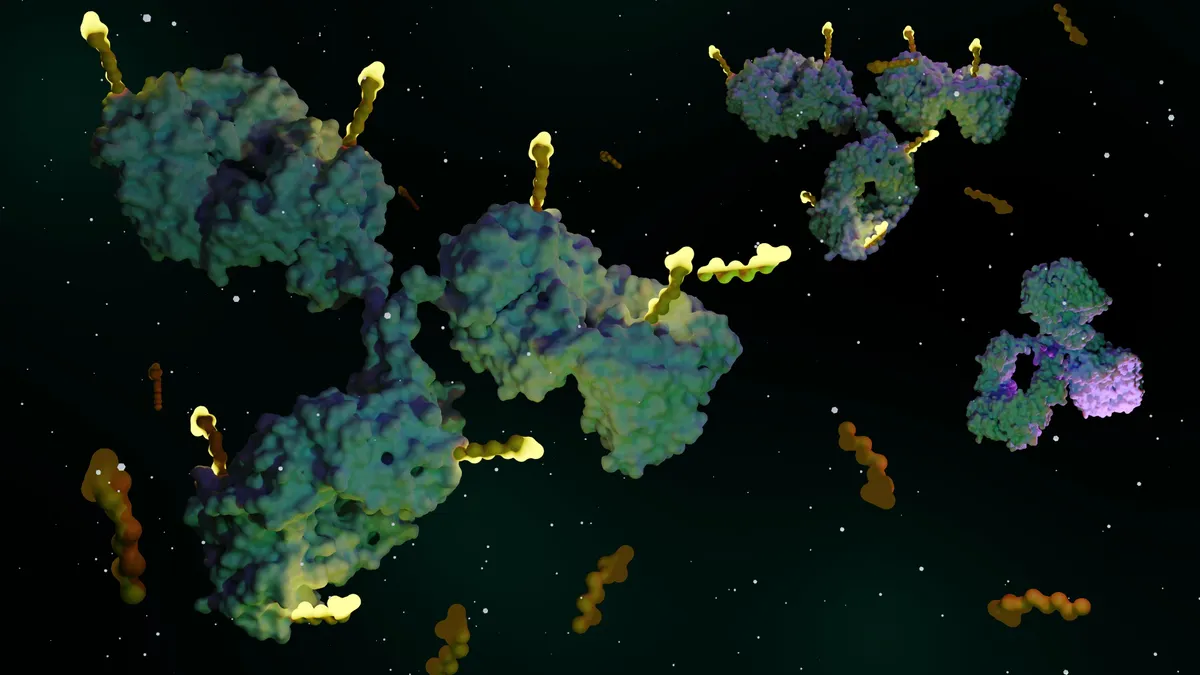

Rather than manipulate Tregs with a cell therapy, Zag is developing bifunctional antibody drugs that shepherd antigens — molecules that can trigger an immune response — to the thymus. Once there, those antibodies engage with the body’s natural machinery for inducing “tolerance” to the delivered antigen, so Tregs don’t see them as a threat.

According to Kulman, Zag's method hasn't been possible up until now. “Nobody has figured out how to get a systemically delivered agent to [the thymus] and do what needs to be done,” he said.

Zag’s first attempt to prove the approach holds merit is a Type 1 diabetes treatment called ZAG-101. In Type 1 diabetes, the body mistakenly attacks the beta cells in the pancreas that produce insulin. ZAG-101 is meant to undo this process by bringing pancreatic beta cell antigens to the thymus, which can then teach the immune system to recognize them as friendly. The goal is glycemic control, said Cole, formerly an executive at SalioGen Therapeutics and Bluebird bio.

Zag’s funding will help take ZAG-101 into early-stage human testing by the end of 2026. The company is also working on multiple potential programs for other autoimmune conditions, though it has not publicly disclosed which.

Polaris Partners incubated the company in 2022. This year, the investment firm co-led its Series A round in conjunction with the T1D foundation. The venture arms of Sanofi, AbbVie and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals are also among its backers.