Chiesi Group has formed an alliance with Arbor Biotechnologies that gives the Italian pharmaceutical company ownership of an experimental gene editing treatment for a rare kidney condition.

Under the terms of the deal announced Monday, Chiesi will pay Arbor up to $115 million in upfront and near-term payments for global rights ABO-101, which is being studied in a disease called primary hyperoxaluria type 1 and is currently in an early-stage clinical trial.

The collaboration also gives Chiesi the option to license other liver-targeting gene editing treatments from Arbor for rare diseases. The biotechnology startup stands to receive up to $2 billion in downstream payments, as well as royalties, if a variety of unspecified milestones are met.

In an interview with BioPharma Dive, Devyn Smith, Arbor’s CEO, said his company partnered with Chiesi because it is “very committed” to rare disease drug development.

“We didn't want someone to do the partnership, and then a year later, they change their mind strategically and move on to whatever the next thing is,” he said.

Chiesi also represented an attractive partnering option because of its success growing revenue in recent years, Smith said. The group has inked alliances with other biotechs, too, such as Gossamer Bio, and acquired others, including Amryt Pharma.

The partnership with Arbor is driven by “the potential of gene editing to transform care for patients,” said Giacomo Chiesi, the executive vice president of the company’s rare disease division. “We share a clear alignment in therapeutic focus and values, which gives us confidence that together we can advance this work responsibly and effectively for patients.”

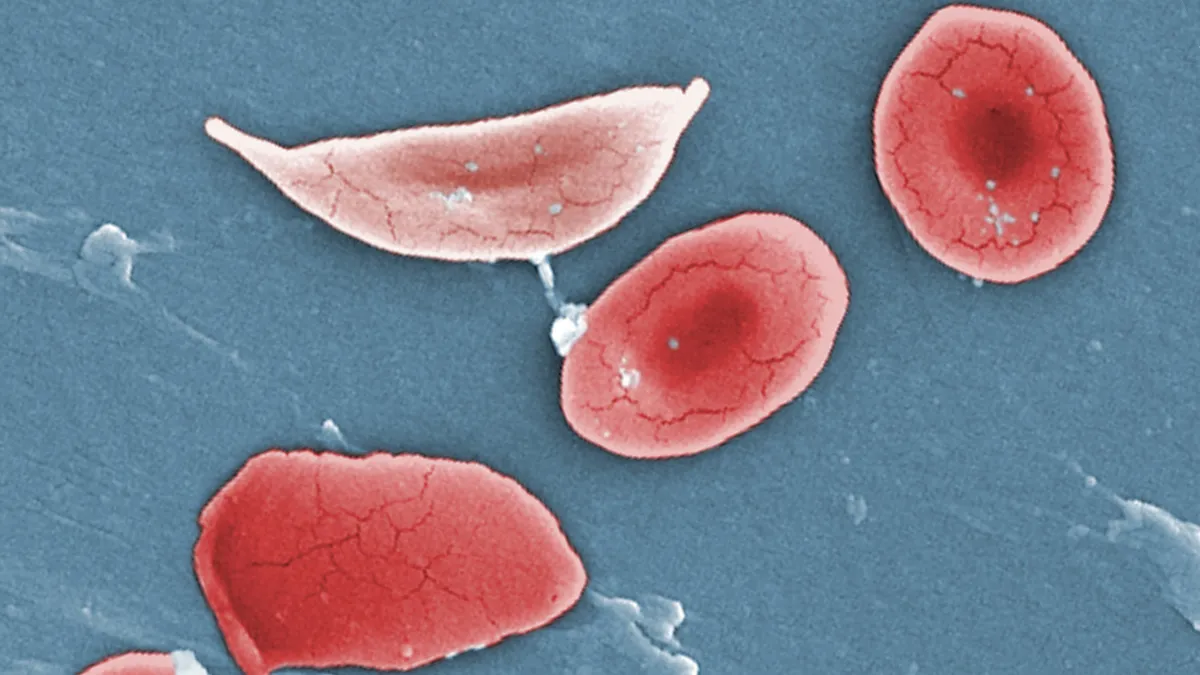

Primary hyperoxaluria type 1, or PH1, is a genetic disease that, according to some estimates, affects between 1 to 3 out of every million people in the U.S. and Europe. The condition occurs when the body produces too much of a substance known as oxalate, which can lead to kidney stones, renal failure and organ damage.

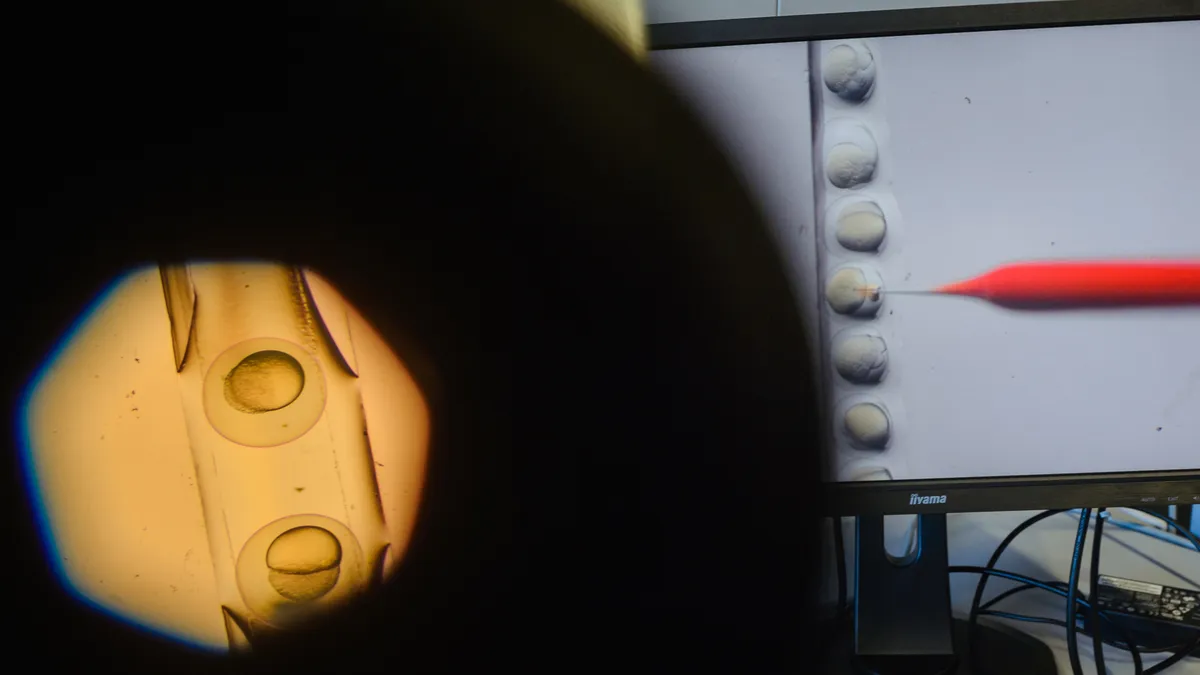

Two medicines are currently approved to treat PH1, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals’ Oxlumo and Novo Nordisk's Rivfloza, and both work by disrupting oxalate production. Both, however, require frequent injections, whereas Arbor’s therapy is meant to be a one-time treatment with lifelong impact.

Developers of genetic medicines have struggled to attract funding of late, as investors have shown a preference towards simpler drugmaking methods with broader market potential. But U.S. regulators have voiced a desire to speed the development of gene therapies for rare conditions, and recently, published draft guidance outlining accelerated approval pathways and new clinical trial designs.

The recent success of a bespoke gene editing treatment custom-made for a critically ill baby with an ultra-rare condition is proof that regulators are open to the modality as a “tool to address and fix chronic disease,” Smith said.

“There is a unique opportunity to continue to think differently in this space,” he said.