A federal advisory committee on Friday postponed a planned vote on whether to delay some newborn infants’ first hepatitis B vaccine dose, throwing into disarray the second day of a scrutinized meeting held to evaluate changes in the childhood immunization schedule.

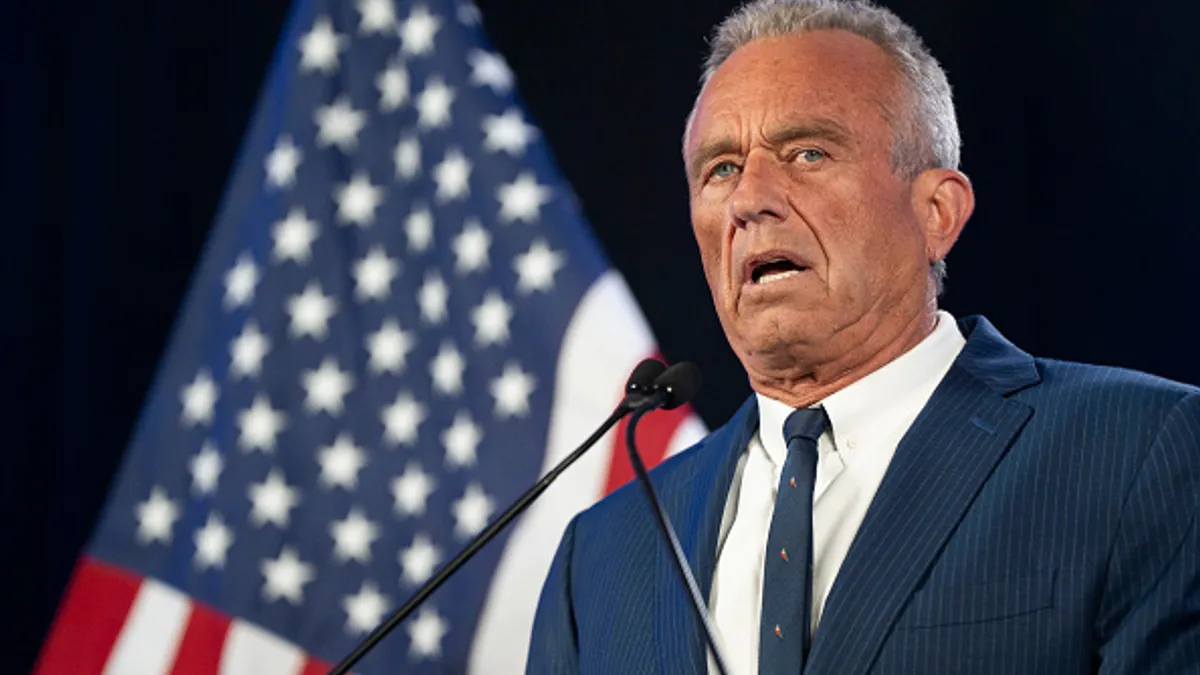

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention panel, which Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. recast to his liking in June and padded further this week, questioned both the safety and the necessity of the hepatitis B vaccine in discussions Thursday ahead of Friday’s vote.

Eleven members of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, or ACIP, voted to table the vote indefinitely, while one, committee chair Martin Kulldorff, voted no. They had been considering whether vaccination should be withheld for at least one month for infants born to women who have tested negative for hepatitis B infection.

However, several panelists raised questions Friday about data presented Thursday, and about the wording of the guidelines they planned to vote on.

“There’s enough ambiguity here and enough remaining discussion about safety, effectiveness and timing,” said Robert Malone, a committee member who in the past has made false claims about COVID-19 vaccines, in proposing to table the vote.

Jason Goldman, a liaison to the American College of Physicians, criticized the process by which the current ACIP had brought up the hepatitis B vote, and urged it to return to its usual process for vetting information through working groups before considering changes to guidelines.

The hepatitis B virus attacks the liver, and can be transmitted from the mother to infant through birth, but also through infected bodily fluids. Long-term infection can lead to cirrhosis, liver cancer and even death.

Vaccines against the virus have been approved since the 1980s, and immunization has proven more than 90% effective in preventing infection in infants, children and adults. All newborns are currently recommended to be vaccinated within 24 hours of birth, followed by two more doses later in life to prevent the disease.

Women can be infected without knowing, but are typically urged to get tested during a prenatal visit. However, insufficient prenatal care, lack of access to healthcare facilities as well as testing and administrative errors, can mean testing doesn’t occur.

How commonly that actually is the case was a matter of debate among the committee during their discussion Thursday. New voting member Evelyn Griffin, an obstetrician and gynecologist from Louisiana, said in her clinical experience, women can get tested and receive results within hours, for example.

However, CDC representative Adam Langer, who gave a background presentation to the committee, noted that some women don’t give birth in a hospital and it isn’t safer to wait to administer the vaccine.

“I have not seen any data that says that there is any benefit to the infant waiting a month. But there are a number of potential harms to the infant waiting a month,” Langer said.

Some ACIP panelists questioned the vaccines’s safety, including Griffin and voting member Vicky Pebsworth, who is also the research director for the vaccine skeptical group National Vaccine Information Center.

Cody Meissner, a panelist and pediatrics professor at the Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine, dissented. “If we begin immunizing children at an older age group, I'm not aware of any data that suggests it's a safer vaccine, because this is an absolutely safe vaccine.”

“I'm not sure what we're gaining by avoiding that first dose within 12 to 24 hours of birth,” Meissner added.

Representatives for Sanofi and Merck & Co., two manufacturers of hepatitis B vaccines, had asked ACIP to maintain the current recommendations. Drugmakers typically provide detailed presentations during ACIP meetings, but Sanofi and Merck were only allowed brief statements Thursday.

Some representatives of outside medical groups that serve as liaisons to ACIP also questioned why the change was even proposed.

Retsef Levi, another skeptic of the vaccine’s safety, said he had decided the committee should reconsider the recommendations.

“What is the reason that we don't have large and long-term randomized clinical trials to actually figure out the answer and not finish the debate?” Levi asked. “We sit here with very lousy evidence and argue that there is no problem whatsoever.”

With the tabling of the vote, it’s not clear when ACIP might next reconsider changes to the CDC’s hepatitis B guidance. The committee is tentatively scheduled to meet again in October.