One year on from the landmark U.S. approval of two powerfully effective gene therapies for sickle cell disease, the treatments have been barely used, a sluggish start that reflects the myriad challenges of launching them.

While some several dozen people with the blood disorder have begun the treatment process for one or the other therapy, only two had actually received an infusion through early December, according to the therapies’ developers, Vertex Pharmaceuticals and Bluebird bio. That’s because the process typically lasts at least several months, involving a precise choreography of medical consultations, preparatory treatments and bespoke manufacturing of the two personalized therapies, called Casgevy and Lyfgenia.

Martin Steinberg, a hematologist at Boston Medical Center, said his center had expected to infuse four or five people with one of the therapies in 2024, and maybe a dozen or so a year going forward. Now, however, he thinks that outlook was too optimistic. “While we've had plenty of patients come to us, getting them through the screening process has taken a little bit of work,” he said.

Slow beginnings for new medicines, especially ones as complex as Casgevy and Lyfgenia, aren’t anything new in the pharmaceutical industry. But the plodding uptake over the therapies’ first year on market stands out more starkly against their dramatic benefit, which can be described as something close to curative.

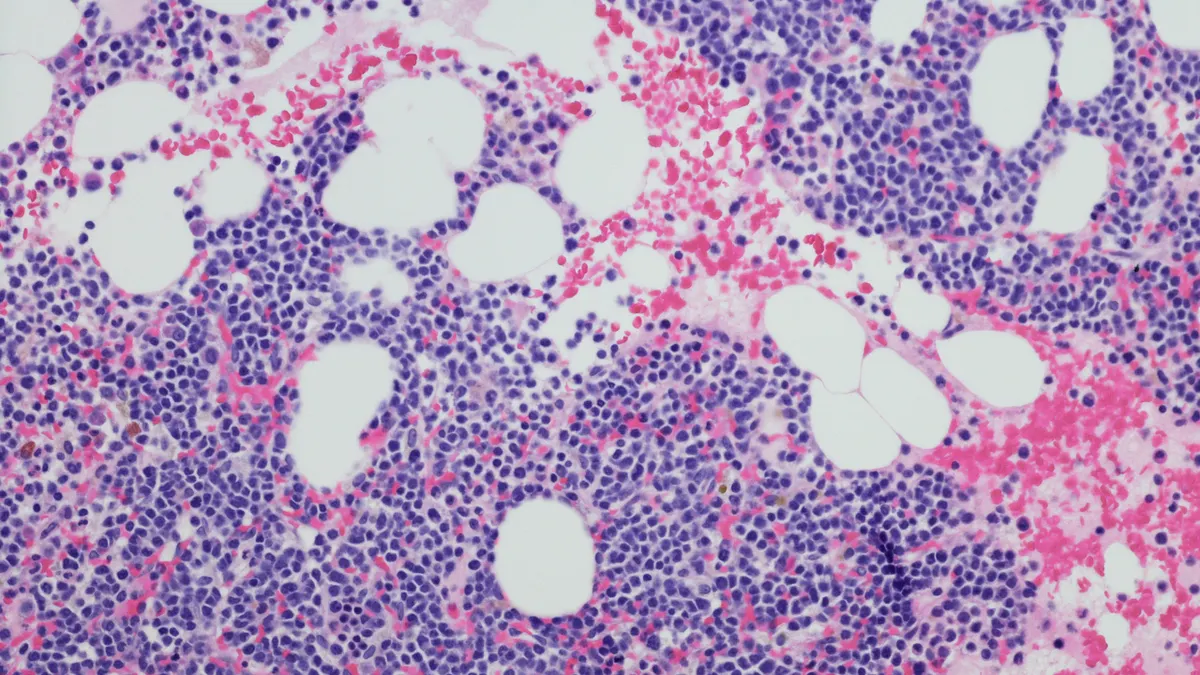

Neither therapy directly fixes the gene mutation that causes red blood cells to warp into sharp-edged scythes in people with sickle cell disease. But through genetic engineering of a patient’s own stem cells, Casgevy and Lyfgenia introduce — in different ways — clever workarounds that improve the health and function of red blood cells. In testing, both therapies generally eliminated the debilitating pain crises people with severe disease routinely experience. As a result, those trial volunteers were able to discontinue blood transfusions and stayed out of the hospital.

Updated trial data presented this weekend at the American Society of Hematology for Casgevy and Lyfgenia show their effects to be meaningfully durable.

The promise of a cure comes with significant trade-offs, however. Treatment with both therapies requires several hospital visits and, all told, a patient’s journey from first evaluation to infusion can stretch as long as a year, depending on how quickly each step goes and whether it’s successful. One step, preparatory chemotherapy with a drug called busulfan, is particularly difficult to bear and can cause infertility. Lyfgenia’s label warns of the risk of blood cancer.

“It’s a complicated process,” said Akshay Sharma, a pediatric hematologist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital who helped test Casgevy. “It's not just the patient preparation and manufacturing of the product that takes time, but [also that] centers have to be accredited. Everything from resources to staff and training has to be completed before you can even enroll a patient.”

Vertex and Bluebird have steadily qualified more and more centers to administer their sickle cell therapies, with Vertex now counting 33 as activated in the U.S., and Bluebird 50. But half of U.S. states still don’t have an accredited center that can provide either Lyfgenia or Casgevy, according to maps posted by the companies online.

Many of these hurdles were anticipated upon approval of both medicines, and the slow rollout hasn’t surprised executives at either company, who had set expectations for gradual launches. Both Vertex and Bluebird predict use of their therapies will grow as more treating centers grow accustomed to providing them. Treatment numbers will climb noticeably in the next few quarters, too, as the dozens who began preparations this year move ahead with infusions.

Yet even as barriers come down, the choice of Casgevy or Lyfgenia may not get easier for patients, who have to process an avalanche of new information and weigh the risks they’re willing to tolerate.

At the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s CuRED Clinic, for example, people with sickle cell meet a range of specialists, including hematologists, transplant experts, psychologists and social workers.

“Families walk away with just a treasure trove of information,” said Alexis Thompson, the chief of CHOP’s hematology division. “There are times when we can tell families are almost overwhelmed with the amount of information they have in front of them. They need to pause and think about it.”

Thompson said interest has been high, though. “Overall there has been mostly enthusiasm, some apprehension, but absolutely engagement.”

Conversations also cover the cost of treatment. Casgevy’s list price is $2.2 million, while Lyfgenia’s is $3.1 million. While doctors say insurance companies are generally agreeing to coverage, patients and their families can still be under the impression they have to pay the therapies’ cost. “Some have taken themselves out of the running because they perceive they can’t afford this,” said Thompson.

There’s also hesitation around new treatments, especially in the sickle cell community. “There’s a lot of not only misunderstanding, but also mistrust of the medical research establishment in general among patients with sickle cell,” said Sharma, of St. Jude. “Just because there is a fancy thing that got approved last year, you wouldn’t expect everybody to run towards that to receive it.”

Indeed, sometimes consultations about Casgevy and Lyfgenia become opportunities to fine-tune treatment with other drugs like hydroxyurea, Thompson said. Or patients may be interested in gene therapy, but opt instead to enroll in one of several clinical trials testing newer, experimental medicines.

Other patients may not be good candidates for Casgevy or Lyfgenia, either because their disease is not severe enough, or because they may not be able to easily endure chemotherapy conditioning.

“You wouldn’t take somebody who's having mild disease, and was well managed on their own medications,” said Sharma. “Demand is limited to the number of patients who have severe disease, and that number is not a lot.”

Some 100,000 people in the U.S. are estimated to have sickle cell. Vertex and Bluebird believe somewhere between one-sixth and one-fifth of that total population may be eligible for Casgevy and Lyfgenia, but only a slice will likely seek them out in the first few years.

Steinberg, at Boston Medical Center, believes the current gene therapies will remain something of a niche product for the time being. “As we get more skillful at getting patients through the process, that won’t be as much of a stumbling block. Maybe we will be able to do one a month or so [at Boston Medical Center],” he said. “But it’s still too early for us to know if this is going to be realistic.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to clarify the timing by which the first two sickle cell patients had received an infusion of either Lyfgenia or Casgevy.